Now, the Avengers . . . the reason I like the Avengers is a much shorter conversation. It’s the Marvel book for people who really, really like their meat and potatoes. Sometimes it’s a $4 Reno strip steak and sometimes it’s a filet mignon, but by god if you belly up to the table for a hearty meal you will walk away full.

While it’s very easy to argue that the X-Men were in context a lesser effort by Lee & Kirby, the Avengers probably shouldn’t even make that list. It’s the most obvious thing in the world, after all, and was long before National even convened the Justice Society in 1940. Just put all the popular guys (and a girl) in one book and have them fight stuff . . . together. Worked for the Argonauts, worked for the Matter of Britain. If you doubt the perfunctory nature of the early Avengers stories, rest assured their actual origin as a team involves the Hulk undercover as a clown robot. Also, “origin” is probably putting it too strongly: Avengers #1 is simply the first time these people meet each other. Captain America climbs aboard in issue #4 and that’s the first time the book exhibits a pulse. It’s still a great story - a perfect reintroduction to a character who was most likely unfamiliar to the vast majority of their readers, complimented with gratifying daubs of pathos and topicality. An early highlight for the line.

Avengers #4 is a perfect summation in one of both the the appeal and the limitations of the premise. At its most basic the Avengers is a workplace drama starring a rotating cast of people who have one of the worst jobs on the planet. Every time the book gets stale you can always upend the ant farm and throw in a few new specimens. Cap was the first new member and the drama of his introduction provides a replacement for the conflict with the Hulk that frames the series’ very beginning. Suddenly the team is an actual ensemble instead of merely a squad of fighters. When its done well, therefore, the Avengers offer the same pleasures as any other long-running workplace entertainment: set up a group of strong personalities, give them a common purpose, watch them bicker and make-out for years on end. These pleasures are not particularly bound to the premise and certainly not to the genre. It doesn’t have to be character driven, although it often is to more of a degree than is acknowledged. Sometimes the book eschews any reference to the long-running subplots of the core Avengers family, and there have been long stretches without any founding member present. It’s such a bog simple premise you can do just about everything with it.

The problem is, you can do just about everything with the Avengers, so long as you’re content for “everything” to mean the Marvel Universe and its precincts. If you’re not already in some way invested in the Marvel Universe as a discrete object you probably have little to no interest in the Avengers. Without prior investment in Captain America and his haunts, his return to said haunts will elicit little pleasure - until, of course, the marketing copy gets to work at manufacturing prior investment from a whole cloth. It isn’t the book for stylistic visionaries, and if that’s where your interests lie you will probably remain unswayed by any poetic evocations of the Buscema / Palmer team. And in all fairness the continuity of those core characters is pretty complex after half a century, in no way bound together by any common theme. If you don’t like those specific characters - Wonder Man, the Wasp, and the like - you will find little purchase for years at a stretch.

So yes, I understand why the appeal of the concept for many has been limited through the years. Leastways until around 2004, at which point the traditional Avengers jazz was dialed back considerably. That’s the cutoff because that’s when Marvel decided they could make a lot more money with the Avengers if they took away the characters people disliked and added more characters people liked. Crazy, I know. If the characters you liked actually were Wonder Man and the Wasp, well, you were shit outta luck.

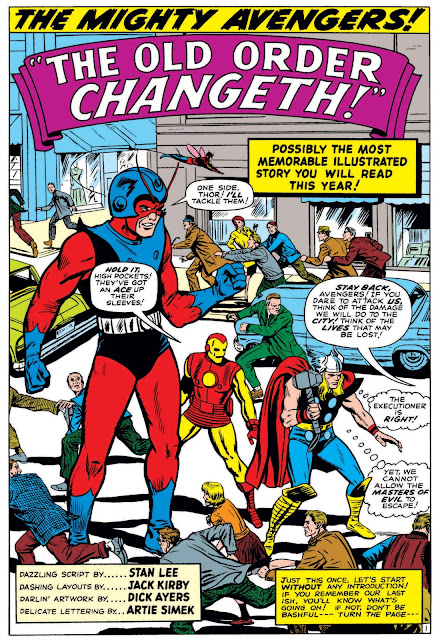

You know by now, or you should: at heart I’m a hopeless traditionalist. Tradition can in this instance be a simple joy, manufactured out of of months and years instead of decades or centuries - but kids are suckers for just that kind of thing. If those blatantly cornball aspects of superhero comic books hold no appeal you will almost certainly remain unmoved by any recitation of “the old order changeth,” and nothing I can say will sway you to the contrary. Never forget Stan conjured that shit out of a whole cloth - the first time Tennyson's phrase was used in this context that “old order” was all of fifteen issue young. He did it because it worked.

Now, as I alluded, the problem - there’s always a problem. Of course there’s always a problem. Ah, well. The “problem,” such as it is, appeared in the aforementioned December of 2004 when Marvel launched New Avengers. Brian Michael Bendis’ reboot of the team eschewed almost all the traditions, saving the presence of one founder and Captain America (who isn’t a founder but is granted founder’s status in voting and procedure), in favor of a team composed of Wolverine and Spider-Man. There were also a few new additions to the team who were, if not quite sales powerhouses, popular characters in their own right previously not associated with the franchise, like Luke Cage, the Sentry, and the Jessica Drew Spider-Woman. With moody art by David Finch and a focus away from traditional Avengers foes in favor of shadowy conspiracies and decompressed action, the series accomplished what had seemed impossible for my entire lifetime. Not only were the Avengers selling better than the X-Men, consistently and not just a bump, for the first time in decades, the Avengers were suddenly cooler for the first time in . . . forever.

The success of the original run of Bendis’ New Avengers was a remarkable thing at the time and still. In hindsight it doesn’t seem like much of a gamble, but then again neither does Ultimate Spider-Man. The success of that series forced Brian Hibbs to eat a bug after it made it to 100 issues of publication, and for that at least, I was there eating that bug too. I read the first half-dozens issues of Ultimate as they dropped and it was the sleepiest damn thing on the shelves. Stopped reading after the origin because it was so lackadaisical. Turns out people were hankering for just that thing. The further gamble a few years later of letting him cross all the red lines to vivisect one of Marvel’s most consistent, if not strongest, performers turned out to be not even a gamble at all. It remade the company, and if you think I’m exaggerating you weren’t around.

It was a marvel, pardon the pun, to see the company cohere so fully and so enthusiastically around a new house style. Whatever adventurousness had fueled the early years of Quesada’s tenure drained as they realized the power of crossovers with the eagerness of early man discovering fire. It was only a matter of time once the success of New Avengers had been metabolized for House of M to be announced, and from House of M the seeds for the next decade of X-Men stories sewn like so much salt. From House of M in 2005 the Avengers in turn were on to Civil War and Secret Invasion and so on down the line until, finally, the streams converged again in 2012 with Avengers vs X-Men. That crossover represented the end of an era for the company, coming at the tail of almost a decade’s worth of Avengers stories by Bendis as well as almost a decade's worth of X-Men plotlines stemming from House of M. It was the last monster of its kind at the company until Hickman’s Secret Wars upended the apple cart in 2015. The scale and impact of that crossover was sufficient to have effectively swallowed all memory of Axis, the medium-scale crossover that emerged from the pages of Uncanny Avengers and preceded the Secret Wars by a mere half-year.

At this point it is necessary to mention that beginning at least with House of M there developed a sense of grievance on the part of a certain segment of the readership who believed Marvel to be intentionally sidelining the mutants in favor of the Avengers. It’s generally a good idea to react with skepticism to these rumors as they almost never have any basis in fact. Fans are always resentful, its what we do. I resent the fuck out of Rogue wearing a red costume, for instance. That and a nickel will get me a cup of coffee. Was there a specific plan on Marvel’s part to torpedo the X-Men, at any point ever? Almost certainly not and I think the idea can be dismissed down the line. Businesses tend not to want major product lines to sell less, especially given the supposed slide begins before Marvel Studios had released a single film and before any purported rivalry between those later movies and the Fox X-Men films (or the Sony Spider-Man films, for that matter).

However, with those very important caveats added, I have already indicated that I just don’t think the company understood the books very well during this period. They put them together in a crossover with the Avengers - House of M - after the Avengers had leapfrogged position on the sales charts, and one team limped out of that crossover in a severely diminished capacity. How was that supposed to look? New Avengers pivoted from House of M to Civil War and in that period cemented its status as both center of the line and epicenter of a new house style. The X-Men pivoted from House of M and the Scarlet Witch muttering “no more mutants” to The 198 and Decimation. House of M happened during Claremont’s last run on Uncanny X-Men and he didn’t stick around long enough to do anything with the premise. Doubt it held a lot of interest for the master. Ed Brubaker followed with a solid year of space stuff, already teed up by Claremont, that was itself overshadowed by the contemporaneous and far more well received Annihilation events. On the adjectiveless X-Men Peter Milligan dealt with some of the fallout of the event, which in practice meant a year of them sitting around the mansion surrounded by Sentinels. That’s the stretch where Gambit becomes a Horseman of Apocalypse, everyone’s favorite. No one wanted to do anything, no one could do anything with the post-House of M status quo. It sat there more or less inert until literally 2007, two years after the fact, by which point none of the core X-books were still being written by the same people who had been writing them in 2005 during House of M. Which means, in essence, the storyline was from almost the very beginning an inheritance shepherded by editors, primarily Axel Alonso.

Oh, wait, I’m sorry, I forgot something - Joss Whedon and John Cassaday’s Astonishing X-Men! Pardon my forgetting. That was the company’s big attempt to pump up the X-Books on the tails of the Morrison era. First issue of that dropped half a year in advance of New Avengers #1, coincided with Claremont coming back aboard Uncanny from where he had been during the Morrison years, holding down Extreme. The marketing copy for Whedon’s debut was rapturous in anticipation of a well-executed “back to basics” move by a then-beloved nerd celebrity writer. With almost two decade’s hindsight the run was a dismal failure. Instead of a bold new direction for the books as a whole Whedon arrived with a boondoggle about space aliens convinced Colossus was destined to destroy their planet.

There was in his sterile fan fic no spark to kindle further stories: he came on board to play with the toys and put them just the way he liked them. Then he got bored and took four years to put out twenty four issues of a monthly comic. The first issue of Whedon’s Astonishing saw print the month before Avengers Disassembled tore that franchise down to sprockets in 2004, the last issue hit shelves the same day as the final chapter of Messiah Complex in early 2008 (X-Men #207), already during the buildup to Secret Invasion. Additionally, the actual final part of Whedon’s story shipped even later than that, in a Giant Sized special that saw print in May of that year. It had gone from new flagship to irrelevant curiosity in, oh, the amount of time it took to ship five monthly issues in 2005. Which is still better than the four they shipped in 2007.

It was hard not to see that a judo maneuver had been performed. In the 90s Bob Harras split the books off into a walled kingdom all their own, at a slight remove from the quotidian goings-on of the mainstream line. The removal was never really to anyone’s benefit but Harras, but it stuck. New management at the turn of the century kept the arrangement simply, one imagines, out of inertia. But then the world turned upside down and the Avengers started selling better. Suddenly the walled kingdom set off in its own exclusive corner was just set off to the side, period. Civil War was an immensely popular story in which the X-Men barely appear, save for Wolverine in his capacity as an Avenger. There’s a tie-in miniseries that features the X-Men gloating about the fact that, for once, the problem has nothing to do with them. They get to be the law-abiding bystanders sitting on the sidelines shaking their heads at the neighbors. One imagines it must have been very satisfying for the mutants in the moment, but probably less so sitting home on Saturday night when everyone else was out getting absolutely demolished at the cast party for Civil War #7.

To the enduring surprise of anyone who remembers the Before Times, the Avengers under Bendis never wavered from their place at the top of the charts. He stayed on those books for eight years and in that time not only finished the initial run of New Avengers but also restarted the book in a slightly more traditionalist mold in 2010 - albeit still with Wolverine and Spider-Man, only this time fighting once again Kang instead of The Hand. Of course, that was all still before the movie, before 2012 and before the Avengers became the most popular superheroes in the world. Whedon had a hand in this, as he apparently found it more gratifying to direct movies than finish scripts in a timely manner. This wasn’t even the New Avengers, mind, but the classic knobs - Hawkeye and Black Widow! Even the god-damned Vision and Scarlet Witch became stars. The movie versions didn’t exactly play up traditionalist aspects of the franchise, however. Made the team an appendage of SHIELD. I believe it lacked the style and grace of the Hulk pretending to be a robot pretending to be a clown.

The Avengers aren’t supposed to be cool. It’s supposed to be a book for wonks and oldsters. That the team is a bit square has always been part of the charm. The movie Avengers aren’t square. The movie Avengers aren’t harried adults juggling shitty personal lives, and possibly even outside careers, who have to fight with city planning and get yelled at by the mayor and deal with tabloid reporters. All those quotidian hassles are missing from the movies - the same hassles that help distinguish public superheroes in the Marvel Universe from gleaming demigods at an Olympian remove (or perched in their moon palace). There’s a peculiarly New York attitude towards celebrity at the heart of the most traditional incarnations of the comic book Avengers - a depiction of superheroes as celebrities consistently framed by a pejorative understanding of fame. This isn’t celebrity as an avatar of distant glamor but a picture of fame as a real-life hassle whose presence creates traffic jams and necessitates expensive repairs. Superheroes roll through your neighborhood like wrecking balls.

A major difference between the Avengers and so many similar teams, for much of their history, has been the manner in which the Avengers purposefully choose to submit to the indignities of fame and inconveniences of bureaucracy. In those humbling gestures they of all their spandex brethren at times bear the greatest resemblance to actual civil servants. They get up in front of the cameras to introduce new members every time as if to say, “these lovely schmucks are why the Holland Tunnel is going to be closed for repair next month. AM Shock Jocks across the Tri-State area get your ‘Blunder Man’ material ready, it’s really not ‘if’ but ‘when.’” Even Bendis’ New Avengers did the press conference.

So with all this in mind? Really not hard to see why X-Men fans at the time may have felt aggrieved. If you grew up in a world where the X-Men were the dominant retail hegemon the very idea that the terminally dorky Avengers might one day surpass them both in sales and the world of multi-billion dollar movie franchises seems perverse. I love the Avengers and it seems perverse to me. Sometimes the old order changeth a bit too much.

Now, keep in mind that the era leading directly into House of M was particularly fraught for the X-Books. The violent counter-reformation that ushered out Morrison’s run saw a brief period in 2004, around the launch of Whedon’s Astonishing, during which Chuck Austen was writing both main X-Men books. Insults heaped upon insults. Whedon was brought in to provide a bold new direction but he did not succeed and that failure impacted everything around it. Claremont and Milligan were sent in to replace Austen on the two main titles and staunch the bleeding, but the books had no direction during this interregnum and neither of those writers lingered past 2006.

Certainly House of M provided that direction, but it was not a direction organic to the books themselves. While again, I want to stress that I don’t believe for one moment the company was trying to sabotage the books, they couldn’t have picked a better plan to convince a certain breed of conspiratorial-minded fan that they were indeed trying their level best to do just that. The irony is that on paper it looks very much as if the Marvel brain trust were trying to give the mutant books what the mutant readers emphatically wanted: a strong direction with a long-term arc that would allow the books to regain focus and remain self-contained while also in theory enabling for more interaction with the wider Marvel Universe down the line. In practice what they got was, indeed, a strong, editorially-mandated direction that in practice more resembled a blind cattle chute into which they could shunt ambitious creators for the next seven or eight years. From the outside looking in was hard not to conclude that a rudderless period for the mutant books in the early aughts led the company to codify some of Harras’ worst tendencies in the name of stability.

As someone who at least in theory liked both the Avengers and X-Men the period was quite confusing. I was cold on the mutants for years at a stretch and didn’t at all care for Bendis on the Avengers. Although I will concede he grew into the book he never grew on me. He never grew out of any of his worst tics in terms of static storytelling and dialogue, and while Alias and to a degree Ultimate Spider-Man were able to make a virtue of the approach I never warmed to it for the Avengers. He got lazier with his plotting as he went, with Age of Ultron serving as the absolute nadir of that immobile tendency. He has very little interest in the practical aspects of fight choreography, a puzzling blindspot for someone who has written action stories for over two decades. Do these sound like very old, very practiced complaints? Well. I’ve certainly made no secret of my feelings regarding his shortcomings as a writer of superhero stories. I’ve been complaining about him in public for all of those two decades now. One of my very first pieces in The Comics Journal was a review of his Daredevil. There’s a chance I have been complaining about Brian Michael Bendis longer than you have been alive. While I have no real dog in the fight of who sells more comics it is nevertheless puzzling to see your favorite book hit its commercial peak by jettisoning everything you love and doubling down on that thing you already dislike.

Which brings us back, again, to Uncanny Avengers. Because you know all that stuff I said before about how significant the book was to the X-Men as a franchise, in theory if not in fact? Well, for the Avengers the release of this series was also the first time since 2004 the main books had been written by someone other than Brian Michael Bendis. Uncanny Avengers launched alongside Jonathan Hickman's reboot of the core Avengers books and the beginning of Bendis' run on the X-Men, and in that context was set up at least ostensibly as a new flagship equidistant between the company's two biggest franchises. (They also launched Al Ewing’s Mighty Avengers soon following, which I mention for the sake of completion even as I acknowledge it as another of many very promising ensemble pieces launched by Ewing to little or no sales response. He has deserved better all down the line.) In marketing if nowhere else Uncanny Avengers represented a new beginning for both teams. In practice, having no connection to the much larger-scale stories in Bendis' and especially Hickman's runs meant Uncanny was sidelined almost the moment it left the gates. The Avengers Unity Squad encounter neither the outlaw Cyclops of the post-AvX period nor intersect a single convergence in the build up to Secret Wars. They all met up for Axis but would probably prefer not to talk about it. (Do the Uncanny Avengers ever show up during the Bendis X-Men run? I tried to remember and subsequently stopped trying to remember.)

At this point its probably worth mentioning that Hickman’s run was in no way shape or form defined by classical tendencies. All of the parts of the Avengers that resemble an old house shoe, the parts to which my Pavlovian fan instincts respond, are precisely those parts that seemed to interest Bendis only a little and Hickman not at all. While there is much to recommend about Hickman’s time on the books its also a singularly terrible Avengers story in which over the course of about three years the most powerful heroes in the Marvel Universe slowly transform into super villains. It’s a story where Dr. Doom saves the day. No Tennyson in its soul, save perhaps a few grace notes allotted Thor along the way. It’s a dirge about the end of the world written by someone who doesn’t particularly seem to like the characters, which is a strange affect to pick up from everything the man has written. Outside, of a few refreshingly sentimental bits of his Fantastic Four. He doesn’t seem to like most of his characters - leastwise the work-for-hire folks - and even if the results can be interesting it’s still a weird look brah.

Does he? Does he love these shards of valuable IP? Does that matter? No idea! I’m old and out of touch. I like to have my hand held like a wee bairn.

The less said about the Bendis X-Men, leastwise by me, the better. I remain baffled by almost every single decision made at every point in that run. By the time it finished it seemed to me barely even begun, so little had anything in that sequence actually mattered - a few character pieces had hit, perhaps. Iceman came out of the closet, a positive development that unfolded in a less than salutary fashion, if memory serve. It has its defenders, just as every X-Men era, and I won’t go out of my way to antagonize them any more than I did at the time. Which was a considerable amount. Jason Aaron’s Wolverine & the X-Men on the contrary was precisely the remedy for years of dreary diminishing returns. A lighter book focused on a younger ensemble cast having wide-ranging adventures across the Marvel Universe? Just the thing at which the franchise always excels but to which it rarely commits.

(Oh, yeah, I checked, the Avengers Unity Squad show up in All-New X-Men #12, have a brief encounter with the time-tossed Original Five X-Men. A plotline I’m still trying to get my head around! It’s been almost a decade. I hope to soon arrive at comprehension.)

So, finally, again, with trembling fingers, we approach the actual first issue of Uncanny Avengers . . . such a strange artifact! The main launch out of one of the biggest crossovers in industry history, an inflection point in a publishing schedule that had reached the end of a long planned arc and was just then beginning another. The book is the last in a chain of dominoes that began when Grant Morrison was brought on to revive the books in 2001. He killed a great deal of mutants and then also made a considerable number of new ones. For a number of reasons Morrison left the franchise in unquestionably enervated shape and they fell into a period of uncertainty after Whedon’s run failed to materialized coattails. The overreaction to this malaise combined with the sudden contemporaneous surge of the Avengers franchise pushed the company to commit to long-term structural changes to the mutant books. The end result, coming after a period of great creative freedom and no small experimentation, was the placing of a straightjacket across the X-Men, committing them to an extended period of maintenance in service of an untenable status quo. During the same period the resurgent Avengers titles enjoyed a long period of commercial ascendency before themselves entering a lull around the end of the decade. It is true both that people had grown generally bored with Bendis’ Avengers and that the post-House of M status quo had run its course in the X-Men books. Avengers vs X-Men enabled them, as much as possible, to shake the proverbial ant farm across the line. But from that perspective its hard not to see that Uncanny Avengers was already at its genesis a throwback to the preoccupations of a previous decade, spawned as it was from the sustained metafictional and commercial conflict between the company’s two strongest franchises. In addition of course to a rather hellacious fictional conflict. So many threads converge here and they also end here.

Not only was the book an extended crossover between the X-Men and Avengers but between their histories as well. Bendis' run on the X-Men for me was marked by a rather strange unwillingness to engage with large parts of that history, which maybe wouldn’t have stood out so much if the run hadn’t at the same time been generally preoccupied with the theme of changing history. (A good rule of thumb for reading Bendis is to remember he always wants a tummy rub after referencing an old comic that didn’t come out when he was 12. Thinks he deserves a treat for it.) Hickman meanwhile certainly felt and feels comfortable rummaging around the entirety of the toybox, but not as I said with an eye towards any nostalgic reverence. His commitment to making sense of all the continuity, not just the stuff in which he is personally interested, is one of his more admirable traits. There's a degree of respectfulness to that approach that seems cousin both to Claremont's scrupulous sociality and Mark Gruenwald's friendly rigor. Bendis could take notes.

But only to a degree, as Hickman’s approach can sometimes feel clinical and purposefully contrary, whereas at his worst Bendis’ enthusiasm for his characters still shines through. (At least the ones he likes.) Enthusiasm in comics can often serve a necessary concession to progress, at least to judge by the spotty track record of fans getting to write their most favorite characters. Regarding the Avengers, the argument could definitely be made that after an extended period of the books being one specific thing from one specific writer (desultory spinoffs notwithstanding), it was for the best they try something else entirely at their first opportunity. Hickman was definitely the man for that in the main line. But that still left fans of the Avengers qua the Avengers somewhat hungry, despite the rather half-hearted return to the more traditionalist elements of the late Bendis era. Anyone who cared about Wonder Man and the Wasp . . .

. . . well, turns out they just happened to be in the same book that was responsible for dealing with the fallout of the last decade of X-Men stories having pushed that line far from its historical thema. The same book that was for that moment during the ascendancy of Jonathan Hickman also torchbearer for the traditionalist tendencies of the Avengers line after a long period of relative disuse under Bendis. And, most importantly for our purposes, the book that marked Rogue’s return to the team she completely tore apart, in the space of a few pages, in literally her first ever appearance, back in 1981. Whew!

It must be mentioned with no small gratitude that neither Morrison, nor Bendis, nor Hickman (so far), showed or have shown any interest whatsoever in Rogue. She was apparently featured as a casualty in Morrison’s original pitch for New X-Men but Claremont saved her from being iced. She shows up for a memorable a cameo during Whedon’s run but otherwise escapes with her dignity. She’s gone when Bendis shows up and completely irrelevant to the design of Hickman’s various programmatic Houses and Powers (again, so far). I would like to sincerely thank all four of these gentlemen for this benign neglect, from the bottom of my heart. I don’t know how she managed to hit four cherries in that lineup but she surely did.

The only problem is that in (so far!) passing largely unscathed through the grand reboots of four successive mutant auteurs, as well as being written off the main teams following Messiah Complex, she had and has effectively passed beyond the X-Men. She doesn’t have a place in the pecking order, she’s fairly unique for that position, and more than any other superteam in existence the X-Men really need a defined pecking order in order to function. Already by 2012 she had become surplus to that story even as they had been chary about committing her to another. Finally they found a new track by pulling on her very oldest thread.

Next: Profound Ambivalence

________________

Oh, What a Rogue

1. I Got No Clue What They Want to do With You (1995)

2. Hello Again (1990)

3. Make it With the Down Boys

I. Everything is Science Fiction (1963-1983)

4. The Journey Ends

Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV (2012-2018)

& A Few Short Words About Carol Danvers