II

Hello Again

Perhaps there is a disjuncture in the idea of fandom - this being for the moment a discussion of fandom. For its faults fandom remains the difference between living culture and dead lines in an archive. Fandom performs transubstantiation, changing the bare materials of art into something new that exists entirely outside the control of the artist or, it should be noted, the copyright holder. Fandom has become the process by which aesthetic artifacts are transformed into social currency through discourse and action.

I’ve long bristled at the label of fan, even when young and far less critical in my ardor. There seemed something servile in the notion of fandom, an association enhanced by the industry’s constant baiting of the fanboys themselves throughout the late 80s and 90s. Who signs up for that kind of abuse? A fool, clearly. Of course, that passive aggressive resentment towards audiences is fairly common in the arts. Any number of Hollywood satires or literary farces attest to the noble tradition of biting the hand that feeds, as does Lobo’s denim vest emblazoned across the back with “BITE ME, FANBOY.”

The dilemma that broke me upon its horns was a conflict between self respect and material reality. I hated being a fan because I knew I was a fan. I knew in that admission lay ownership of a stereotype of self-effacing and uncritical loyalty - undignified loyalty - against which I chafed, and against which frankly I still do. How have I resolved this conflict? To a degree I probably haven’t and never will. But to a larger extant, I think, the conflict is resolved by defining the object of loyalty - of what are you a fan of? Are you a fan of creators or characters, or are you a fan of a brand? I grew up with “Make Mine Marvel,” but grew out of that attitude long before I was ever going to outgrow the comics themselves.

The problem in a nutshell is that the corporations that own and control the fates of our most beloved fictional characters do not have those characters’ best interests at heart. They have certainly never considered the best interests of creators. This isn’t a new situation, this is how the business has always been run. How all business has always been run since corporations got in the IP business.

The two most significant events during the twilight of my comic book reading adolescence were the formation of Image Comics in early February of 1992 and the death of Jack Kirby just two years and a week later. The convergence of these two events was the cause of creators’ rights. The narrative that surrounded the Image uprising was simple enough even the early 90s comics press could put it together: generations of pioneers had been hung out to dry - Kirby’s name invoked almost every other breath - so Todd and Rob and Jim were, as Jay might put it, overcharging for what they did to the Cold Crush. Kirby’s death two years later, and after a period of extensive industry carnage, seemed to signal a punctuation mark. The death of a giant to mark the end of an age.

Were the Image founders completely sincere in their repeated framing of their corporate power move as a blow for creators’ rights in an atomized industry? I believe so. That they turned around - some of them within the year - and replicated something similar to the factory system they had fled is ironic but not perhaps hypocritical. (That two of them would remain intimate parties to Marvel’s corporate deliberations for many years to come is another matter entirely.) They still maintained control of their shit, and everyone else who came to their company retained control over their shit as well. What they did with that control was indicative of their character, whether they wanted to launch a media empire to compete with the one they’d recently left or just wanted the freedom to create independent of oversight. Erik Larsen is still going on Savage Dragon and Jim Lee is still going on covering for Bob Harras. To every man his own heaven.

My problem was that I took seriously what I read. When I saw what Stan had done to Jack, I couldn’t feel the same way about Stan. How can you forget that? You can’t. But it made sense because these facts were all of a piece, part of a pattern that added up to an entire industry implicated in the miasma of its foundation. It also fit with what my parents told me about the world, who it worked for and how it worked. They did it to Jack, they did it to Steve, they did it to Jerry and Joe and Bill too . . . I wasn’t even a teenager before I had learned both that the sausage was made by people and that people were the sausage.

So I knew from very young not to be loyal to a brand, because a brand is just a company. Companies don’t deserve loyalty, people do. And furthermore, that loyalty shouldn’t be absolute either, but dependent on respect. Does it matter, you ask, that supporting creators you respect and following characters you love means supporting a company you have, at times, actively despised for their many and various turpitudes? Well, actually, it does. It matters a lot, because I knew I was a hypocrite for continuing to give money to Marvel. I’ve always known that, haven’t had plausible deniability in the matter since I was twelve.

Fandom has become another kind of identitarianism. The mass loyalty towards Marvel and DC as brands qua brands is a patently destructive phenomenon in that it levels all nuance to achieve binary stasis across mass culture. Very Manichaean on all sides. I believe very strongly that if you love or have ever loved what Marvel does you should be sharply critical of how they do it. Historically and empirically the company has done nothing to earn our trust as readers or consumers.

Do I love Marvel? No. Do I love many things Marvel owns? Oh yes, a great many. I have found that a profitable disjuncture, inasmuch as I have learned a great deal over the years from worrying the open sore in all its nuance. Profitable as fodder for writing, perhaps, if terrible for the soul.

Trust that I do speak from love, if not a love for the brand. Why else would I be angry?

It’s too easy to drown in bile. Too facile an exit from responsibility. Aren’t we here for something more?

We are. Let’s talk about love.

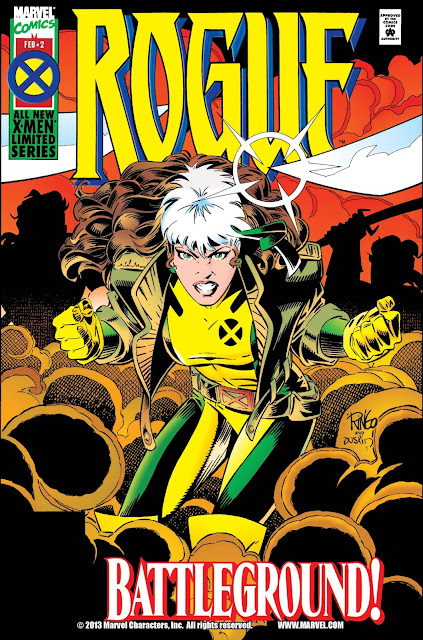

As mentioned earlier, I joined the X-Men right at the outset of an extended absence on Rogue’s part. She was gone. The few times I’d seen her were in passing, or flashback. That was when she had that late 80s ‘do like she personally killed half the ozone layer. Just another super chick with music video hair. (Still hate that late 80s hair for her, incidentally.)

And then I picked up Classic X-Men #44, early January 1990. Same month my dad chopped off part of his hand in a snowblower accident. My first real introduction to Rogue. That issue of Classic reprinted #138 of Uncanny from late 1980, Jean Grey’s funeral - the denouement of the Dark Phoenix Saga, immediately prior to Kitty Pryde joining the main cast. It’s the one where Cyclops is especially lachrymose. I know, really narrows it down. Rogue wouldn’t appear at all for the better part of a year, and wouldn’t join the cast of Uncanny X-Men for a few more years after that. So she’s not in the main story of that issue of Classic, but she is in the backup.

The first four years of Classic X-Men carried backup features, because every dollar not spent on an X-Men book was a dollar you could spend on Green Lantern. Nobody wanted that. Certainly not if they could entice the most loyal readers in the industry to double dip on stories they’d already read. “Her First & Last,” as such, was a weird pick for an introduction to Rogue. It was a new backup in a reprint book, for one, and a childhood flashback for another. It wasn’t even written by Chris Claremont, but Ann Nocenti.

Nocenti is one of the most talented people to ever work in comics. We didn’t and don’t deserve her. She didn’t write very many X-Men stories, but the few she put her hand to proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that she understood these characters intimately. Hired by Denny O’Neil in the early 80s and mentored by Mark Gruenwald for her earliest writing and editing jobs, her success is also testament to the measurable ways in which the company became less progressive as the 80s turned into the 90s, and women and people of color found far less purchase than just a few years previous. By 1987 Nocenti eventually earned the coveted cursed chalice of following Frank Miller and “Born Again” on Daredevil. What should have been a suicide mission became a four year run considered by some superior even to Miller’s, if clearly less celebrated.

(I’m “some,” incidentally.)

I wish I could remember what it felt like to read this story for the first time. I know I read it over and over, because this was one of my favorite issues of Classic. Much of it is flashback and recap about Jean Grey’s life - great for newcomers because it more or less tells you everything you need to know from the book’s first incarnation in the 1960s. You never forget the first time you meet Factor Three. I’ve always loved comics that recap other comics, a strange affectation that comes from appreciating the dense and wonkish reading experience bred by that kind of intertextuality. (Also why I was attracted to medieval literature, incidentally.) I liked learning about the characters almost as much as I liked their actual stories. Took more time to read those comics, and I appreciated that.

What was I thinking when I read “Her First & Last” for the first time? Perhaps I didn’t think anything. I just remembered it. Remembered every beat of this strange, sad story. Returning to it for this essay proved a shock, because while I remembered the story vividly I know I couldn’t at the time have articulated why it meant so much to me. It hit me now as if I was reading it for the first time. How the fuck do we process these things, if something as significant as the reason I like my favorite character was a secret my pubescent self buried close to their heart and forgot about? How is it possible to have remembered a story but forgot the impact crater it left?

The original impulse behind wanting to reread Claremont’s X-Men was actually social. By early 2020 I had been through a period of prolonged intense seclusion while maintaining what was more or less my “day job” of taking care of my parents for the State of California. (I haven’t had a day off from round the clock care of my dad for . . . over a year and a half? Is that right? That can’t be right.) This was during the first stages of pandemic, mind you, so I wasn’t entering seclusion at that point so much as merely confirming an additional period of seclusion. From my perspective the world was finally joining me. As such I wanted to read something I could talk about with someone else. Wasn’t that always part of the appeal? Everyone read it because everyone read it.

If you’ve ever read anything of mine you know I’ve been - well, how do we put it? Estranged from myself. Emotionally speaking. I’m used to being surprised when I go back by the strength of an emotional reaction in hindsight. But I wasn’t expecting, nor was I in any way ready for, the absolute tsunami of subconscious bullshit that poured out of my brain when I started poking the box marked “X-Men Feelz.”

It was certainly a surprise to me that where was such a box, even if in hindsight it makes complete sense. Perhaps you have such a box yourself, whether you know it or like to admit it. Or, hell, maybe you revel in it. There was just so much water under the bridge, you know. In so many ways. For both me and for the comics industry, my life and the lives of the X-Men. Easy to pack it all away. Couldn’t efface the bond, try as I’d like.

Because we did have that bond. I say “we” because there’s a good chance if you care enough to read these words you share it too - a feeling as if perhaps these weird characters were just a little bit more than the next schmucks on the shelf, in some intangible way. And that achievement, building a stable of players vivid and durable enough to carry on a full thirty years and counting past the master’s first leave-taking . . . well. That kind of achievement lingers with a body.

Oh yeah, thirty years - did you notice? Thirty years this summer from the end of the Claremont run. As of this writing.

Just because he left didn’t make us stop loving the characters. And Marvel knew that. They knew they had us by the short hairs and weren’t about to let go. If they didn’t know before the Image founders left - if there had been any doubt whatsoever about the solid commercial appeal of the franchise in Claremont’s wake - it was shelved once they realized the shambling zombie books they pushed out with spit and bailing wire through the lean years of the early 90s still sold well, if never better, than the books they published when they gave a fuck. But well enough in the moment to mask the general downward trend of an industry wide slide.

The lesson was, if we bought X-Cutioner’s Song we’d buy anything.

So of course the books kept getting worse, as the company kept getting worse. Enthusiasm generated by periodic signs of life - Joe Madureira’s extraordinarily influential run, the still-beloved Age of Apocalypse - invariably led to further disappointment. Then after the turn of the century and a decade of Harras-led strip-mining the books shifted into different gears under new management. They caromed down the next decade through a sequence of ill-advised decisions that left me feeling, when I checked in, as if I simply did not recognize the characters anymore. It wasn’t just one bad story or unintended consequence of an editorial mandate, it wasn’t one bad run or even a number of them. There were still decent, occasionally good books published. Just like always, the books were good when they hired good people to do them and weren’t worth wrapping fish when they didn’t. But every new creator good and bad was still stuck dealing with the same roulette wheel of editorially mandated new directions since the turn of the century, new directions that sometimes left very little room for individual characters to express the kind of agency they need to thrive. OK, this month we’re on a rock outside San Francisco Bay . . .

Do you see why I lost touch? Why I began to harbor grave suspicions that the men (only ever men since the early 90s) in charge of Marvel misunderstood the X-Men on a fundamental level, characters and metaphor alike? Even as I continued to read out of habit, even long after my only real excuse (not illegitimate but perhaps unsatisfactory) was professional? I never felt quite so estranged from the rest of the Marvel line. But with the mutants I lost the plot. By the time we hit the second decade of the millennium . . . AvX, the motherfucking Bendis years (shudder) . . . I had no problem tapping out for a while. Still don’t know how the Original Five got home, I’m assuming they were probably killed by the Scourge first. Justice is served!

Pum-SPAAK!!!

It’s worth pointing out that it’s natural to lose touch with these things. Most people do let things go as they get older. Some people always get left behind when the new thing that used to be the old thing just isn’t their thing. It happens. Part of growing up is realizing that leaving things behind sometimes just means making room for something new in your life.

But they just kept nagging at me, the X-Men. It seemed more, I don’t know, personal. Maybe that feeling of incompleteness was only ever the phantom pain of the original Claremont run being so violently terminated. When I arrived it was almost over. There was also the added injury of seeing these intimately familiar characters bowdlerized by rabid misogynists in real time as we paid for the privilege. That sense of loss, of estrangement from something important, that hurt. That hurt went into the same closet as all the other feelings of shame and self-loathing that I am stuck carrying from a lifetime of dealing with an industry that advertises its contempt for both its readership and its creators on a daily basis. It’s the latter I can’t forgive. Because I know I’m indicted as well. When will the hurting stop? Perhaps when we are no longer rent by the moral disjuncture of continuing to support companies who do not deserve our respect.

Of course . . . that closet was only one closet in the rather large haunted house that is my brain. There were so many other traumas, serious traumas, far more personally injurious than mere hypocrisy or missed stories. There were other closets.

Rereading these stories has been profoundly disconcerting to me because I’ve been surprised by the depth of my connection to these characters - and one character in specific. Rogue was always my favorite even through periods when I actively avoided the series for long stretches. That’s why Carey’s X-Men Legacy was the book that really brought me back to the franchise even as I didn’t really dig the books’ overall direction. It’s the closest we’ve ever gotten to a Rogue solo series, even if it was still ultimately about her dealing with X-Men shit. It was always the first book I read. Legacy is my favorite non-Claremont X-Men run, and how I rediscovered Rogue as an adult after years of unspoken resentment from being burnt through the 90s. They made me hate my favorite character, putting her through one terrible storyline after another. I mean, come on, people. Joseph. (I’ve filled and am still filling in some of the gaps from the years I missed, but Extreme X-Men is a bit like laudanum in that too much in one sitting will probably kill you. We’ll get there. Baby steps. We’ll do it together and it won’t be so hard.)

It’s embarrassing for me to acknowledge how deeply it affected me to reread the old stories - the first run of Rogue stories in Uncanny, specifically, but also dipping into later series. I didn’t remember how much she meant to me. As simple as that.

Because, when you get down to it - I’ve never had a bond with a fictional character as strong as Rogue. I’ve being reading comics since before I could read. I spent a total of ten years studying literature in undergrad and graduate school. I’ve known lots of characters. I’ve felt connections with lots of characters, just like most people. I’ve spent a lot of time writing about these connections, but also about what I perceived as my own problems relating viscerally, emotionally to fictional characters. I’m uncomfortable with any kind of parasocial relationship. Like Rogue I’m a profoundly lonely person, and have developed a sensitivity to whether or not friendships are real or simply a figment of my imagination, having been stung too often by not being able to tell the difference. It strikes me that devotion to a fictional character is about the most abject kind of parasocial relationship of all. Not even a real person, literal lines on paper.

Perhaps I’m just picking nits because on some level I’m deeply embarrassed about the whole thing. Estranged from myself. Isn’t that what I’m trying to do with my own writing, create some kind of emotional connection with people through my words? What rank hypocrisy.

So of course I wish I could go back and ask myself, circa 1990 - what are you thinking about this story? Do you see yourself? Does that make you uncomfortable - why?

What’s it actually about, “Her First & Last?” Well, it’s about Rogue as a kid - on the cusp of being a teen, after her powers first manifested. It’s not Cody’s story - although, I should mention even as I intend to punt the question, the actual circumstances of Rogue’s childhood years are kind of fraught. Continuity-wise, that is. There’s some dispute because different writers working from Claremont’s template have differed on various details, including whether or not she lived with Mystique before her powers manifested. Some of the comics that purport to answer these comics were written by Scott Lobdell, to add injury to insult.

In any event, this isn’t Cody’s story, this is Freddy’s story. Who’s Freddy? No one, really. Some neighborhood kid Rogue liked to play with. She already knew what her powers did and was already wearing tights and long sleeved shirts that covered every inch of skin. But not yet fully aware what all that really meant. It’s a simple story, really, and a familiar one: Freddy keeps trying to kiss Rogue. Obviously doesn’t take no for an answer. Finally he gets his wish and its more than he bargained for.

It’s not a story about something happening to her, however, or even about poor Freddy. It’s a story about bad decisions.

What was I thinking when I read this story for the first time? Did I understand it? Most likely no. What was I thinking? Probably nothing too profound. I was a kid.

So here’s Rogue, young and happy, with the biggest smile of her life. Rogue doesn’t always smile a lot. She smiles when she’s flying, probably because that’s the only time she doesn’t have to worry about hurting anyone. Riding on the handlebars is the closest she can get to that freedom, for the moment.

The art here is provided by Kieron Dwyer, with inks by Hilary Barta. This is a great combo - Dwyer’s loose, cartoony figures and broadly expressive faces naturally fit with Barta’s supple line. So much can be expressed simply through the variable thickness of a single mark on a character’s face.

Look at Dwyer’s body language for young Rogue throughout the story. Loose and limber, in motion - above all, comfortable in her own body as only a kid can be. She still hasn’t quite internalized the degree to which growing older means saying goodbye to that easy comfort with herself, for her more than anyone else.

But here, in these opening panels, you can’t help but think of Berkeley Breathed. The Bloom County gang spent lots of time crashing into dandelion fields. Breathed always had a much more expressive line than he needed to, given the limitations against which he very vocally chafed. He was a better draftsman than he gave himself credit.

Even given her fending off Freddy’s awkward adolescent advances - certainly exacerbated by her own willfully ignorant persistence in hanging out with a guy who clearly wants to kiss her - it’s all more or less normal. One might even say idyllic. She clearly wants to kiss him too, is the thing. She just doesn’t quite understand how to square that circle between must and can’t.

I mean, can you blame her? Lots of people die never knowing the difference. It’s a hard thing to accept that the unique circumstances of your life will entail different consequences from those suffered by your peers, especially at a tender age. It sets you apart to know that you are different, especially when the difference is invisible. It makes you old before your time.

Enter Mystique.

As a point of principle I avoid referring to Mystique as Rogue’s mother. Mystique was a terrorist who kidnapped an orphan for the express purpose of grooming said orphan to be a terrorist. Like every narcissist Mystique’s purported love is coldly self-serving and purely transactional. Regardless of what their creator may have intended, Rogue dodged a bullet in never having that parentage confirmed (in continuity). What she actually did end up with in terms of parentage wasn’t much better, mind, but that’s another day and another headache.

Mystique is, during Claremont’s tenure, a mostly ineffectual mole in the Pentagon whose greatest achievement was figuring out how to get the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants on the government payroll. (I have also always assumed she embezzled a great deal of money.) She does things for only two reasons: to suit her own selfish goals and because Destiny said so. That’s it. She has no agenda beyond “survival” and “my wife” (Borat voce) and to that extent what little she does in the direction of benefit to mutantkind is purely self-serving, more or less along the lines of well, I don’t want to die in a concentration camp in ten years so I guess I should probably assassinate this guy, because my wife tells me there’s a cause and effect somewhere or other. I believe everything my wife tells me. Who is Mystique, after all, but a Wife Guy gone horribly, horribly wrong? After said wife dies does she not immediately descend into rank sociopathy? QED!!!

Mystique finds Rogue blowing dandelions in the front yard and we can see, immediately - the story is not subtle about showing us - that Mystique means Rogue harm. She is explicitly framed as a threat, cold ivory hand reaching in from outside the panel to disturb the idyll with the touch.

The dialogue through this sequence seems intentionally stilted and awkward, like any young teenager yelling at her parents - “I can too have boys! I can have what every normal girl can have!” Of course, Rogue probably shouldn’t be playing with boys, at least not like that. That’s the worst part: it’s not like Mystique is wrong. She’s also a coolly manipulative piece of shit who doesn’t know how to do anything but immediately try to turn Rogue’s pain into a weapon for her own use: “Your power is special,” she says, “It can be used to help us.”

Note the exchange immediately after Rogue leaves. Destiny counsels Mystique that, essentially, she will come to regret treating someone she ostensibly loves like a means to an end. Despite being precognitive Destiny is also almost always an ineffectual nag. To be fair, Destiny had to live with the fact that she premiered two months after Madame Web (Amazing Spider-Man #210, November 1980 vs Uncanny X-Men #141, January 1981), meaning she was more or less the Garfield to Madame Web’s Heathcliff. The elderly blind precognitive woman X-Men villain was always going to be more popular than the the elderly blind precognitive woman Spider-Man supporting character, but true heads will always know who came first. (Score another for Denny O’Neil, who this essay isn’t even about, but who created Madame Web with John Romita, Jr., in addition to discovering Ann Nocenti.)

Rogue runs away from Mystique, heading for a meet-up with Freddy. She needs to play, have a good time, be with people her own age - but she’s also stuck. She can’t move on. Because that’s precisely the age, right there, twelve or so, when playing kids tend to segregate along more rigid gender lines, going through the early rites of man and womanhood that transpire in social spaces across the world. Simple as apple pie . . .

But that’s not Rogue. She doesn’t get to develop anymore beyond this point in time. And she can’t just keep playing on the tire swing with Freddy. He doesn’t know that, to be fair. He doesn’t know the last dork to pull this trick got put into a coma for the rest of his life.

And this is the difference, right here. She knew what was going to happen and she did it anyway.

Look now, with me, at those two panels of Rogue’s face in the bottom row. No narrative boxes, no thought bubbles - just a few lines on a face to indicate the most fateful deliberation of her life to date. Look at that first panel - eyes fixed on the middle distance, every muscle in her face clenched. She’s running over the dilemma in her mind. So much story expressed through so little.

Then she gets a dare and it’s all over. You can see from the look on her eyes, she remembers - wait a minute, I have the upper hand. I have no reason to be afraid of him and I don’t back down from anyone. Whether she realizes it or not it’s in that moment that she is most like her putative guardian - that’s Mystique’s logic, merely to take as she wishes and be damned with the consequences for anyone else.

But it’s done. In a moment it’s over. She experiences everything he ever was or, truly, would ever be, and leaves him slumped over unconscious.

Rogue absorbs all of Freddy’s memories over the course of two full pages, narrative collages framing the central image of Rogue hanging upside down on a rope swing and in profile. The glow of young attraction is flipped in an instant to violence. Intentional hurt. Violation. “He would have told her these stories slowly, naturally, in time,” the captions tell us, “and she would have revealed herself, slowly, to him . . . but Rogue will never know the pleasure of that journey.”

She lands and the narration relates her thoughts:

Rogue sees his unconscious form and cries. For her to know someone is to rip his mind out, possess it, spit it out again. This is not, and never will be, love. Not for Rogue. A kiss is not a gentle thing . . . She cries for a long time, mourning the normal life she’ll never have.

Have you ever had to do that - kill a part of yourself in order to live?

This is why Rogue is different, even from the rest of the X-Men. In order to survive she had to disassociate herself from her emotions. That’s a living hell. To realize, from a young age, not just that you are different, but that you are different in a way that will dictate the shape of your life, limit your horizons, prevent you from ever experiencing so much of what we consider “normal” life. To be granted at such a tender age not just that knowledge but the additional perspective granted by her powers - the kind of interpersonal perspective and emotional awareness granted by her powers sets her apart. Already at that age she knows more than anyone around her about seeing the world through other peoples’ eyes. Even Mystique and Destiny, for all their prowess. But when knowing precedes understanding people get trapped, traumatized premature brains held in rotting cages stifled by perpetual arrested development.

We get stuck sometimes at the point where we have to protect ourselves. That fits Rogue to a “T”: wise beyond her years in some respects but childishly naive in a few crucial ways. She doesn’t know how to protect herself from people who would never dream of putting her interests before theirs. As such her life from this point spins out of her control entirely. She returns home that afternoon and volunteers straight away for whatever dangerous mission Mystique was intending a twelve or thirteen year old girl to be able to accomplish.

The next time we see Rogue in continuity she’s punching Captain America through a wall in Avengers Annual #10. She has become precisely what Mystique wanted her to be: someone who could turn off the part of herself that felt any remorse in order to strike out at the world at the behest of someone else. A weapon.

And we saw where that got her. Driven mad from isolation, loneliness, touch starved, gaslit about the color of the sky by Mystique, so painfully jealous of the rest of the world she became a Dazzler villain out of spite . . . look. I’ve given Spider-Woman “the business” more than once for having a less-than-stellar rogue’s gallery, but the fact is that she has a rogue’s gallery - and a sizable one - whereas Dazzler had . . .

. . . uh, well, there was Rogue, obviously . . . Enchantress? didn’t she fight Terrax? . . . Robert Christgau? Marvel Unlimited doesn’t want me to know.

Rock bottom looks different for everyone. Rogue’s rock bottom was trying to kill Dazzler. Now, the person I really feel bad for in all this is Dazzler. That’s gotta hurt, to know your one time arch villain - who only ever tried to kill you in the first place because she was extraordinarily depressed - is a better superhero than you ever were by an order of magnitude. Well. That’s just got to sting.

Anyway.

As much as I like the X-Men in many ways, I’m also critical of the premise. I don’t think it means the same things it used to, and I don’t even know if it ever really meant what it was imputed to mean. I’m not here to gainsay what anyone else feels about the books, but to attest for my own purposes that the books’ greatest strength is their characters. When you can hear those characters it still works. When the writers and editors lean on high concept status quo upheavals that deterministically funnel every character into the same situations, the stories can lean repetitive. When the characters don’t have enough freedom to make their own bad choices they become just like all the other long underwear types who do things out of custom. Only, y’know, with more weird conceptual baggage of the type that keeps them from doing actual fun superhero stuff a lot of the time.

“Her First & Last” underlines the degree to which Rogue as a character is a problematic addition to the franchise. Her powers are harmful, not just in the wrong hands or without training. She usually can’t live anything resembling a normal life - the status quo may change periodically, but to permanently get rid of the limitation on touch would hurt her as much as being able to change at will would hurt The Thing. Her powers are a tremendous burden and carry the risk of potentially debilitating trauma almost every time she uses them. This makes her uniquely vulnerable, but also - and for this discussion, just as important - it’s what makes her an interesting character.

Lots of real-life disabilities and diseases are mutations too, after all. The books are often ill-equipped to deal with mutants whose fantastic powers resemble more harmful disabilities, even though plenty of characters exist who could possibly fit that bill. (Rockslide and Glob Herman, I’m sorry you have no junk. That must be profoundly disconcerting.) I mean, perhaps the point should be stated directly: if the limitations placed on Rogue’s life by her powers aren’t a disability I don’t know what is. Does Krakoa have disability accommodations? I’ve still only read a bit, maybe it does.

Plus, of course, there’s the bipolar disorder, a boring old real world disability exacerbated and inflamed by her powers and decades of trauma, clearly defined in the cycles of her violent antisocial behavior. Another thing we share: anger management issues. Like me, the adrenaline from anger makes her manic. She was manic a lot. Bipolars who live like that burn out like candles - cf. DMX RIP. In an early flashback (Uncanny X-Men #203), she describes the thought process behind trying to murder Carol Danvers by throwing her unconscious body off the Golden Gate Bridge:

Ah was so wired from the fight, ah didn’t know really what had happened - ‘cept that, somehow, she’d made me crazy. Ah thought, by gettin’ rid of her, once an’ for all - by destroyin’ her body as ah had her mind - ah’d silence the voices, the screams, the pain, the rage inside my own head.

Notice the slippage there? She starts by saying that absorbing Carol’s mind made her crazy, but then ends by indicating that somehow during the course of the fight Carol becomes identified with all “the voices, the screams, the pain, the rage” she was already suffering. As a result of years and years spent in denial, using violence and adrenaline to self-medicate, scarred by lack of treatment for mental illness and lack of accommodation for disability, constantly disassociating because of around-the-clock gaslighting at the hands of a paranoid narcissist, she arrives at adulthood barely functional.

So, follow me here: Mystique finds a troubled and desperate young mutant and trains her to be a terrorist. Rogue teaches herself to get by no matter how much it hurts, no matter how much it costs to mask her own feelings. It works for a time until, well, she loses her shit entirely and tries to kill the Dazzler. Multiple times. Finally she breaks free from years of brainwashing and - in a rare lucid moment between manic fugues spent trying to kill women on whom she had become psychosexually fixated - arrives on the doorstop of her enemies to beg for help with her inherently destructive powers. Help which is granted, even despite vocal objections from most of the team.

(Usually not mentioned that one catalyst for her change of heart was a fight with ROM where she absorbed a spark of the Spaceknight’s inherent kindness and nobility. Better than lithium!)

That should be a good story, but somehow I can’t help but thinking that the next part matters too, the part where the kid who just made the first tentative steps in the direction of some kind of treatment for her severe mental illness was then handed a thick three-ring binder labeled “People Who Will Want to Kill You Now That You Are an X-Man.” It’s a strange list, basically just a couple inches of loose leaf pages from the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe Master Edition. You know, the one where everyone’s holding up their capes to show off dat ass tho. Biggest entry by far is the Appendix entitled “Chucksies’ Whoopsies,” a catalog of Charles’ personal errors in judgment which might at any moment come back to kill someone. It’s got lots of handwritten notes and some Post It’s sticking out because the information is very fluid.

I’m not saying the business model is fundamentally flawed but I am saying Charles Xavier never met a personal problem he couldn’t solve by raising a private militia of troubled teens. Maybe not such a great idea to index an entire civil rights movement to the mercurial whims of a rich WASP. I tend to like the books the better the further away he is from the story. For a number of reasons, not least of which being he has objectively terrible personal judgment. What is the value of a father figure who is almost always wrong and what’s more a bellicose prick? Who will, and please be advised I’m about to use some “spicy language” to indicate my contempt, abandon his charges at a moments’ notice to go hang out with space bird strange? Like he did in issue #200 of Uncanny?

Yeah, I know. He had reasons. Bet they were good reasons, too. He had to buy a pack of smokes on Chandilar. At least the book gets better once he’s not there to piss all over everyone’s Frosted Flakes.

I don’t have a lot of patience for father figures, I guess you could say. The X-Men as a franchise is stuffed to the gills with father figures working out their father issues by raising private militias, often of literal children. I know it’s the premise, but I don’t really believe in leaders. If you don’t believe in leaders it’s a problematic premise. The Avengers operate as more or less a democracy, with team leaders elected and major decisions made as a group - the JLA and the Legion work on the same principle. The X-Men, bless their hearts, huddle around and wait for one of three people to tell them what to do: the serial liar who was also Onslaught, the guy who left his wife twice - and that’s two different wives - in the most abjectly humiliating ways he could imagine, or Storm. I mean, maybe I’m exaggerating a trifle. But as organizations go the team is rigidly hierarchical in a way other teams seem to actively strive against. Can’t shake the basic association with the schoolhouse chain of command.

And I ask you, is this a good environment for Rogue? After all she’s been through?

Now, if you’re an astute reader you might be expecting me to loop back at some point to a glancing comment a made towards the beginning of the essay, about my dad’s accident back in 1990. But for these purposes the individual circumstances of that accident are besides the point - the point in this case being not one trauma but many. Accidents and incidents from throughout childhood and subsequent years that ring in memory like tinnitus, even as more benign surrounding memories and associations fade. Once you start turning off parts of yourself, you don’t really get to choose after a while what gets turned off. The circuit box got permanently jammed after a lifetime’s worth of weird and traumatic shit, years spent learning to disassociate from the material circumstances of my life, from the onslaught of mental illness and gender dysphoria, and, fuck, various kinds of neuroatypicality just sprinkled around on top like chocolate chips. Well! You know what that does to a body. Driven mad from isolation, loneliness, touch starved, surrounded by people who didn’t necessarily have your best interests at heart . . .

What was I thinking when I read this story for the first time? Did I understand it? Most likely no. What was I thinking? Probably nothing too profound. I think at the time I thought Dwyer’s young Rogue was the cutest girl I’d ever seen in the world. My whole life I’ve fallen in love with girls for looking just a bit like that.

There’s no way I could have understood at the time why the story would mean so much to me so many years after the fact, looking back with three decades experience in the painful consequences of that kind of self-repression. For Rogue, as for me, what seemed such a simple decision in the context of the story is far more fateful in light of the next miserable period of her life, years spent killing the best parts of her because they were the parts that hurt the most. In the process she became the worst possible version of herself. It’s a hard thing to be a kid and realize, to grasp on some obscure level even if distinctly, that you’re different than other kids, and you’re not necessarily different because you’re special but because for the rest of your life the conflicts within your head are always going to seem just a little bit more vivid than the conflicts outside your head. Not something everyone can or wants to understand, especially if you barely do yourself.

Other people have a way of picking up on stuff like that. Rogue masks it well, better than I do. “Rogue has a way with men,” we hear repeated in various formulations through her history. All because she’s a tiny bit aloof, somewhat distracted, and definitely impatient. Of course, the fact that’s she’s a stunner doesn’t hurt. But it’s her attitude. Generally disinterested. Drives men wild. Even though it’s just Rogue being Rogue. Always something on her mind, even if she mostly keeps her own counsel. Always feels alone in a crowd.

There’s a disjuncture in the idea of fandom, for me, because disassociating myself from my genuine love from these characters - specifically Rogue - was nothing more than collateral damage from a decades’-long war against my own mental health. Just another inconsequential memory. A fraction of a thought.

But not every memory resurfaced singes the brain with the uncanny recognition through time of myself. The disjuncture is with me, my discomfort with the vulnerability required as an entrance to fandom, a problem I’ve written about for years and come no closer to exsanguination. Letting go of critical detachment, professional or academic, is still not easy. What is fandom but a public profession of love, and what is a public profession of love but an admission of vulnerability? Exposure of a soft underbelly, the one missing scale?

What else am I trying to do but maintain a safe distance so as to avoid being hurt again?

Running into Rogue again like this, taking the time to catch up with an old friend - well, you know how it is. I guess we’ve both been through the wringer - started strong, ran into some bumpy patches because of bad writing, acted dependably out of character for years at a time. Did the best with the cards we were dealt. After some forty years still all potential and poor execution. Just two more neurotic burnt out xennials who took a wrong turn in the 90s and spent the next decades trying to find the person they could have been. Ravishingly banal, when you put it like that. The great wisdom of middle age is that every day not spent trying to kill the Dazzler is a triumph. Simple as apple pie.

Speaking of forty years - 2021 is Rogue’s fortieth anniversary. Do you know who hasn’t acknowledged that, so far as Google is able to reveal? Marvel Comics. Maybe something bigger is coming down the pike for the fall? Perhaps a line of variant covers with Rogue’s costumes through the years drawn by her greatest artists? I mean, come on, it’s right there. This shouldn’t be so hard.

Weird to think my writing a book about her is more than Marvel’s done yet. You did figure out that’s what we’re doing here, right?

Thanks for reading the first two chapters of my book about Rogue. She means the world to me.