The first volume of Uncanny Avengers carries a great deal of weight - a frankly enormous amount of weight on its shoulders. That the first volume reads as well as it does is a minor miracle. It’s only sometimes a bad book but the impact craters from where it runs into the ditch are visible from orbit. Although it has its problems I don't want to leave you with the impression that the story has nothing to offer. Perhaps it seems more interesting in hindsight precisely because it was so thoroughly mooted by circumstances. The book itself stood out as stylistically and thematically conservative next to Hickman or Bendis on either side. It left a bad taste in peoples’ mouths due to thematic elements which occupy a fleeting amount of panel time. It's a mixed bag. A very mixed bag.

Rick Remender had been knocking around the company for a few years prior to landing the gig, with highlights his run of Uncanny X-Force and the “Frankencastle” saga that spun out of the Dark Reign promotion. Whatever else the man may be guilty of he still made the Punisher into a giant green Frankenstein, and for that we will be forever grateful. (No joke: his Punisher is pretty great.) Now, there are many forms Uncanny Avengers could have taken, including one dealing more directly with the events of Avengers vs X-Men. However with the exception of the dispossession of Professor X’s deceased brain that launches the plot there’s no direct connection to AvX. (Bendis’ X-Men books dealt with some of that more granular aftermath, to be fair.) The form Remender’s book did take was that of a sequel to his Uncanny X-Force, more specifically that series’ Apocalypse plotline. This wasn’t a bad idea by any stretch. The series is more generally concerned with taking the X-Men to account for the disastrous consequences of becoming ever more insulated from the rest of humanity. There’s no single storyline of the era that typifies the moral quagmire of the period than Remender’s X-Force so it makes sense to start there.

Remender’s Uncanny X-Force was technically the third relaunch of X-Force this century. The first was an unmemorable six issue mini from 2004 featuring a reunion of series creators Rob Liefeld and Fabian Nicieza. The second ran from 2008 to 2010 and featured an updating of the concept, leaving behind Cable but keeping roughly the same attitude. Written by Craig Kyle and Christopher Yost, the series earned a reputation for Grand Guignol violence and gore during a particularly bloody minded period in the franchise history. The series was, after all, about Wolverine leading a black ops squad of hardened killers (and, uh, Rahne Sinclair) operating out of the aptly-named Utopia. Although that probably doesn’t seem from the description like my kind of thing, Clayton Crain’s delightfully gruesome, kinetic art elevated the enterprise significantly. The follow up, Remender’s Uncanny, launched the same year the previous iteration wrapped, with a slightly different focus. Whereas the previous X-Force had been a mostly humorless exercise in frothy grimdark, Remender’s follow-up was both more droll and more dynamic, although it still faltered in places. The art throughout is often superlative, with top-shelf work from the likes of Esad Ribic, Phil Noto, and Jerome Opeña.

Before getting lost in the thicket of plot and character, it’s worth pointing out that the art throughout most of the run of Uncanny Avengers runs the gamut from very good to superlative, and precisely none of my criticism of the series plot and themes reflects on it. That the series looks so good in places is primarily down to MVP Daniel Acuña. His work took a while to grow on me, I admit, but grow on me it did. The panels can be cramped sometimes but generally the pages read well and the characters are very expressive. He colors his own work, and exceptionally well. Also draws a very nice Rogue. The opening arc is drawn by John Cassaday. I haven’t always cared for his latter-day material - a staginess always present in the early work comes to dominate, particularly in his X-Men. Figures look stiff to me, a tendency I didn’t notice so much on Planetary but which became distracting for me beginning with his Astonishing. Steve McNiven pops in for a few issues in the middle of the run, solid as ever. We perhaps underrate him on the basis of his consistency.

Please, make no mistake, when I say that Uncanny Avengers was about taking the X-Men to account for their actions during the Utopia era, I mean that in the most literal way. There’s a scene where Captain America finds out the X-Men have been running a black ops squad (more than one, actually) and he reacts about as well as you could expect. Certainly further fuel for discontent among those X-Fans inclined to feel the slight, but it worked for me. It’s not a subtle message but one the story well conveys: the X-Men actually did cross important lines, lines that people acting outside the law shouldn’t be able to cross with impunity, and there needed to be consequences when it happened. That there weren’t consequences at the time is how the original problem grew into an even bigger problem. There’s probably a deleted scene devoted solely to them explaining the plot of Necrosha to Cap, blinking rapidly as if he’s had a hemorrhage.

However even if the series is rather unambiguous in that framing, the narrative is also careful to show at every step the degree to which the Avengers themselves become compromised and lose perspective as the stakes become increasingly personal. There’s no small hypocrisy involved here and it becomes clear the moment the Grim Reaper shows up - he’s Wonder Man’s brother, after all, zombie and occasional partner to Ultron, and he hates anyone standing next to dear Simon as a matter of general principle. X-Men villains don’t have a monopoly on vendetta. That seems a fair shakeout after years of conflict: the Avengers are unambiguously right that the X-Men need to hold themselves to higher standards, but those same Avengers also learn the very swift lesson that wading wholeheartedly into X-Men problems often means arriving too late to find Captain America solutions. That means having to live with the consequences of bad decisions made in the heat of a crisis.

It doesn’t help that as the story proceeds it becomes clear that Thor is every bit as implicated in the unfolding atrocity, and for infinitely more petty reasons than the extremities of survival to which the mutants are regularly pushed. To his credit, however, Thor has always been more of an ally to the mutants than is generally recognized, due in a large part to Claremont & Simonson’s 80s collaborations. He demolished the Marauders during the Mutant Massacre, which is certainly more than you did. The series reveals an old school rivalry between Apocalypse and Thor dating back to the first millennium, as well as the existence of the great axe Jarnbjorn, a weapon capable of killing Celestials. One imagines the existence of such a weapon should have come up at some point during the Fourth Host of the Celestials (ca. Thor #300), but one imagines in vain. To date no one has been called to account for this misstep.

The X-Men have a hair trigger because they’re used to being dismissed and expect it as a rule even in the face of genuine good faith, and are additionally so used to operating outside the law they have no perspective on their own blind spots. The Avengers are defensive because they feel guilty for allowing the problem to go so far and are already implicated in ways they did not initially recognize. They do not understand the degree to which their public status insulates them from the lived conflict that remains the X-Men’s everyday reality - and this is true even for putative mutant Avengers like the Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver. They’re increasingly over their heads as the internecine conflict entangles them. Pretty solid character work, as far as it goes. Basically the same dynamic the liberal establishment maintains with every marginalized group.

Where are the devils? Oh, the details! In broad strokes these ideas make sense. In specific the work misses as much as it hits. As with most stories hinging on conflict between the Avengers and the X-Men dating back to the beginning of time, the premise of the tale depends partly on characters acting selectively out of character. Here at least the series has an excuse of sorts for everyone acting brittle and defensive - the X-Men have just lost a war. They shouldn’t have been fighting the war in the first place and they lost because they lost perspective. That the X-Men acknowledge the Avengers were in the right, and lose a great deal in so learning, doesn’t help it go down any smoother in the aftermath when the latter essentially begins dictating terms to the former.

To add to a combustible premise, the Scarlet Witch joins the cast and has to deal with what happens when Dr. Doom frames you for genocide and every other mutant on the planet has a hard time letting go of that. That means in practice lots of arguments between her and other mutants, specifically Rogue. She’s on the scene and just happens to have a lot of anger following the murder of Professor X at the hands of one of her most trusted friends. Sadly for Wanda, Rogue has no other place to put that anger than the woman who spent her entire career scrupulously avoiding ever fighting for other mutants. Cue hijinks? Not really, no.

At the risk of inviting modern cliche the first stretch of Uncanny Avengers deals with the immediate aftermath of massive trauma. Each character is processing what happened during AvX - to say nothing of everything else that happened across the previous decade. To add to the theme Captain America experiences ten years in another dimension in between issues of this run, due to events in his own series which was at the time also being written by Remender. Even if those specific events are immaterial to the present story the sense of shock and loss is palpable across the cast. So perhaps we forgive a bit of the abrasive tone in that light, given that the characters are the worst versions of themselves and at times it’s not particularly pleasant to read. More on that in a moment.

The good parts of Remender’s Uncanny are good. The problem is that the book isn’t just made of good parts. The good parts are, roughly, the parts dealing with Kang and the Apocalypse Twins, and the bad parts are those dealing with the Red Skull and what eventually becomes Axis. Split down the middle you find the character work. Some of the interpersonal work is very good. Some of it is so bad it broke the internet when it was published. Will we be exploring the issues involved? Only in the most abstract. After almost ten years the dated discourse on prejudice seems even more dated, even as the shape of the controversy makes a hell of a lot more sense.

Let’s talk about the good before the bad. Will we be getting to the bad? It will be mentioned in passing . . . What I like about the series, unambiguously, is the way it works hard to dovetail the histories of the two franchises. I recognize some older heads might take umbrage to liberties here. If you’re one to glance askance at recent retcons you will probably roll your eyes mightily at the news that Kang and Apocalypse, with his Clan Akkaba, have been at war for a very long time. But it makes perfect sense, takes nothing away from what is known while building on what we have already seen. Particularly 1996’s Rise of Apocalypse miniseries that already tied En Sabah Nur to the reign of Pharaoh Rama Tut. The good Pharaoh was one of Kang’s early identities, but just one, and oh boy are there a few. The links had been there all along. It’s an additive development that introduces a more organic connection between the two teams. Immortals and time travelers are natural enemies, everyone knows that.

(If you read Young Avengers you’ll learn even more about the connections between Kang’s identities and the Scarlet Witch’s family, and if you read Young Avengers: The Children’s Crusade, you’ll learn about how the aforementioned Dr. Doom was the mastermind behind the aforementioned House of M. Sort of. It’s complicated. You should probably just read Young Avengers, it’s pretty good even if it doesn’t have Rogue. Pobody’s nerfect!)

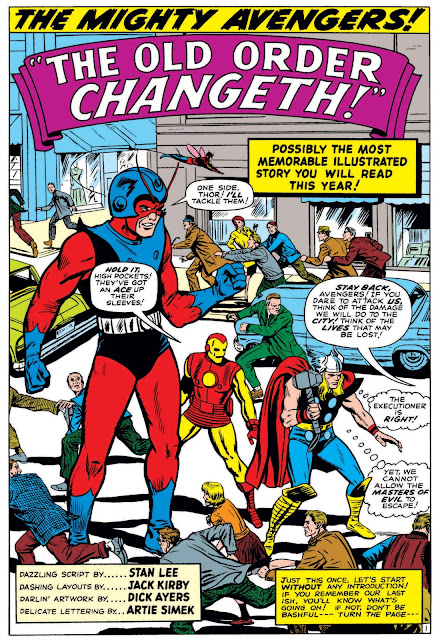

This is all part of a long chain of events leading back to 1963’s’ Fantastic Four #19, the first appearance of Rama Tut during the Fantastic Four’s first journey to ancient Egypt. That one adventure has been elaborated and expanded by later developments involving Kang, Dr. Strange, the West Coast Avengers, Moon Knight, an alternate Fantastic Four, our Fantastic Four (again), apparently according to the Wiki at some point Killpower (sans Motormouth??? That’s even a thing?) . . . a whole lot of people, in other words, have traveled back in time to one specific moment in our ancient history. Which just happens to also be the precise moment En Sabah Nur first manifests his mutant abilities. Weird coincidence, I know! The idea that all these subsequent iterations across fifty years are still, at heart, crossover tie-ins to one issue of Fantastic Four that was published during the Kennedy administration, well - that’s my favorite part of the whole enterprise. A discourse community spread across half a century dedicated to riffing mountains out of seeming molehills, all playing a game of one-upmanship to see who can fit the most angels on the head of a pin. My people, whether I like it or not. Whether they like it or not.

Another development I enjoyed was the marriage between the Wasp and Havok. It made a lot of sense, honestly - he’s just her type, a blonde himbo with great power who’s also juuuust a little bit less capable than she is. Havok gets points from me simply for not being his brother. They even have a kid together, the disappearance of whom remains a dangling plotline from the series that I do not believe has yet been pulled. But could be at any time! One imagines there are multiple parties who might be interested in the fruit of a union between the Summers clan and the extended family of Henry Pym. Not like both families don’t have enemies obsessed with genealogy and inheritance. Just saying, don’t come to me crying when you get your wig permanently flipped down the road - it’s all fun and games until Ultron shows up on Krakoa calling Jean Grey his auntie.

Perhaps Jonathan Hickman remembers that Ultron and the Phalanx once had a very successful and mutually advantageous partnership. Seems like the kind of thing he might have made a Post-It note about, you know, for his graphs. See, it’s not like I don’t understand Hickman. On the contrary, I think I understand very well the way he thinks. He’s Grant Morrison if Grant Morrison had constructed an eccentric mystical philosophy not out of the Illuminatus! trilogy but the Chilton Auto Repair Manual for a 2004 Chevy Aveo. I see the thought process but the results he kicks out are unerringly pessimistic in a way that makes me thankful I never use Reddit for anything but video game tips. Anyway, as I write this Hickman has just announced he is stepping away from writing any of the X-Men books he relaunched, ostensibly because Marvel and his fellow creators were reluctant to move on from the first part of the initial outline of his run. (The fact that he finds his creator owned work more fulfilling probably plays a role as well.) I think we can reasonably infer from the available evidence that the reason he left was in fact the editors’ refusal to allow him to use Ultron, because they said the evil robot was “too scary.” Perhaps we can get a rumor site to run with that.

The third connection between franchises - after the rivalry of Apocalypse and Kang and the Summers / van Dyne marriage - involved integrating Rogue directly into the ongoing soap opera of the Avengers, the saga of which Remender picked up from the later Bendis era and did his best to nurse in Hickman’s dereliction. Rogue now has more in the way of a personal stake in the lives of Wonder Man, the Scarlet Witch, and the Wasp - to say nothing of Carol Danvers - than to all but a handful of X-Men. Rogue had already been absent from the main stream of the mutant plot for years by the time she joined the Avengers, set off to the side in Legacy. Although she wasn’t absent from the X-Books during her tenure with the Avengers neither was she a driving force. There are whole generations of X-Men she barely knows, and as I’ve continuously alluded, her sitting at an angle to the teams’ traditional leadership structure is a mostly unacknowledged sore thumb in the status quo. Think about the fact that she’s a non-entity on Krakoa and absent from leadership despite having just >checks notes< led the Avengers for a couple years and saved the world multiple times, most recently as of Hickman’s launch during 2018’s No Surrender crossover. That’s also where she straight-up murders Corvus Glaive, puts her fist through his chest on-panel. Number one guy of none other than Thanos himself! You’d think that would at least give people pause prior to dismissing her from consideration for leadership. But she’s busy being married. Ahem.

They made a great job in the years following House of M of showing precisely the ways in which the character was misused by her team and underutilized by the company. Her joining the Avengers was an overdue development. It certainly makes more sense in a vacuum than Wolverine. Her problem with the X-Men is that she has no patience for the team’s traditional management philosophy, top heavy and riven by ideology. When first offered a leadership role in 2000 - during the early days of Claremont II - her first reaction was to demur. Power holds no appeal. She talks to Xavier as an equal and feels no qualms at holding him to account when he falls short, isn’t afraid of Apocalypse, dismisses Mystique entirely. Very little connection to any Summers or Grey family drama - Rogue didn’t even meet Jean Grey until she’d been an X-Man for half a decade. Her and Kitty Pryde hated each other from the moment the former joined the team, despite their later ostensible civility (more on that, as you can imagine, later). Her great contribution to mutant liberation doctrine was the golden insight that Magneto really just needed to shut up and look pretty. Maybe he should smile more? Among the X-Men she appears at times the sole principled anarchist in a house split down the middle between frustrated liberals and pious tankies.

Now, however, she’s had Wonder Man living inside her head for a year, ergo has been inserted into a de facto love triangle - the obstacle between him and the Scarlet Witch, who if you recall, already got on really well with Rogue. Also on that tip, her relationship with Magneto created natural antagonism with his once and former children - I know that’s been changed, but seems too much a load-bearing pillar to remain permanently altered. (Ditto for Franklin Richard not being a mutant. There are always good reasons in the moment, but in five or ten years those reasons will no longer be applicable. Some people liked Guy Gardner as a Vuldarian. When the Cinematic Universe needs reasons to tie the X-Men to the Fantastic Four and the Avengers those connections will return very quickly.) She led the team against Henry Pym and Ultron at their worst. Part of the Wasp’s arc, from the beginning of the first volume of Uncanny Avengers to the end of the third, was more or less her learning to trust not just the other X-Men but Rogue, specifically. Once Janet does she comes to recognize Rogue as one of the team’s best leaders. They become buddies. Buddies.

To top it all off, of course, there’s her intimate connection to one of the single most traumatic events in the team’s history, a chain of events that began with the truly awful Avengers #200 and was only ever resolved after Kurt Busiek reintegrated Carol to the team at the turn of the century. Rogue wasn’t the reason Ms. Marvel left the Avengers but she was the reason Ms. Marvel retired as an Earth-based superhero for twenty years.

As for the bad . . . well. There were as I mentioned two distinct plots running through the series: one of those plots involved Kang and the progeny of Apocalypse dueling through history and across alternate futures, features the Celestials destroying the planet, as well as a gruesome on-panel death for Rogue. (Don’t worry, she gets better.) It’s a twisty-turny time travel epic whose plot is about undoing itself, a staple of both franchises, albeit in vastly different ways. One team is all about fighting Kang and one team is all about fighting to prevent nightmarish alternate futures, so the story of Uncanny Avengers becomes Kang fighting to undo a nightmarish alternate future. QED.

The other plot featured the aforementioned Red Skull stealing Charles Xavier’s telepathy. In the first place - oh, damn, that sounds like a windup. Hah. I guess it is. The Red Skull who appears here isn’t actually the Red Skull, but yet another version, this one a clone of the original who wakes up in 2012 straight from 1945. Siiiiiiiiggggghhhhhh. Why go with a new variant of a character who already has a few imposters running around? You’re just adding paragraphs to the Wiki. The real Red Skull was last seen as a disembodied spirit at the end of Ed Brubaker’s Captain America run, if I recall the kind of metaphysical dead-not-dead from which any writer worth his salt should be able to weave a yarn of grand return. But nope, we’re doing the clone. Not like the fact that he was a clone was ever really relevant, either. Later on Sin starts hanging out with the clone of her old man, basically more or less going along with the whole thing. One assumes there isn’t reason for her to be attached to any particular iteration over another, can’t imagine a lot of cozy in-jokes in the Schmidt household.

But that’s a small matter, ultimately, as the clone factor is only briefly relevant - a bit of hash for the cataloguers. More pressing is the degree to which the book is devoted to exploring issues of prejudice and discrimination. And, before we get to the bad, it’s worth mentioning that it’s not entirely bad, and the book’s opening arc is probably the best treatment of the theme in the whole series. The Red Skull shows up with Xavier’s brain (or at least the telepathy parts) and starts a race riot in the middle of the city with a few ugly words. Was it supposed to read as “over the top” in context? We’ve been on the other side of the looking glass for so long that the Skull’s incitements have become regular features of our political landscape. Remender gets it right in that the mechanics of demagoguery are every bit as simple as what we see on the page. Simpler, even. In reality the Skull wouldn’t have needed Xavier’s telepathy to gin up a riot against a hated minority, just Facebook.

It’s when the book stops to think too hard that it gets into trouble. Alex Summers is situated as the central figure in this argument, a mutant intimately connected to and yet also critically distant from the traditional X-Men hierarchy. He’d spent a good part of the last decade in space, missing out on much of the Utopia period by dint of spending a season in the cosmic end of the pool. In reality these are precisely the reasons why Havok turned out to be a terrible choice to lead this very public team of Avengers. He is indeed a privileged mutant, able to pass completely for baseline human, and possessing that rarest of rare attributes among X-Men - not just a job but an actual career. He’s an archaeologist! He has an advanced degree and in many respects his day job is better and more interesting than being a superhero. Not the usual X-Men dilemma.

In our real world, the prevalence of relatively privileged specimens in leadership positions at civil rights organizations warps the mission. Respectability politics come into play. All that is actually a great setup for a solo book: mutant who (perhaps selfishly?) turns his back on the internecine drama of that community - and much of that struggle - to return to his awesome day job as globe-trotting archeologist across the Marvel Universe. Doesn’t that sound interesting? Rogue clearly isn’t the only character to be hurt by the X-Men books’ long-standing inability to develop individual characters. It’s like they don’t even exist anymore outside their position on teams. Fans like it that way? Seems terribly sad.

Say what you will about the Avengers, but from the very beginning with Captain America the book has been designed to develop and rehabilitate established characters for further use. It doesn’t always work and can fail spectacularly, as during Bob Harras’ tenure as writer, which “developed” Sersi, Crystal, and the Black Knight so well they were radioactive for a solid decade. (He somehow managed to ruin the Avengers while also simultaneously running the X-Men into a ditch. Impressive.) But this is one aspect of the franchise history that both Bendis and Hickman used well. Both writers introduced pet favorites onto the team who found success as a direct result of getting the call. Remember when Luke Cage and Wolverine seemed terribly off-model for the Avengers? Now they’re mainstays. (Spider-Man and Spider Woman on the contrary had already spent time alongside if not with the team so they didn’t seem that odd to me. Spider-Man had been a reserve Avenger since 1991.) Likewise, during the same period that Rogue served on the Unity Squad Sunspot was also an Avenger for almost a decade, Cannonball for a while with him.

(Shang-Chi joined as well during Hickman’s term but I remain convinced he was a poorer fit than any of these other unlikely additions, at least to judge by how he was used in his first years as an Avenger. I arrive at this judgement from observing that writers started giving him hokey hi-tech gimmicks almost immediately upon him joining. These tech workarounds emphasized in a perhaps unintentional way that the writers may themselves have not understood why he was on the team.)

Anyway. Captain America picks Alex to lead the team based on the fact that he’s a handsome white guy who has led before and already has media training, dating from his tenure on X-Factor in the early 90s. Although it doesn’t really come up in the course of Remender’s run, it’s important in that Havok’s incarnation of X-Factor is one of only a small handful of mutant teams to have ever presented any substantial public face, which they maintained even down to the Avengers-esque press conferences. The X-Men might have done better all along if Chuck had had the foresight to hire a press agent. That’s a big part of Cap’s thinking in putting Havok front and center, in any event.

This worked about as well as it ever has in the real world, which is variable depending on how large a handicap you give someone who is manifestly bad at all aspects of his job. Seriously: name a team Alex Summers has headed which hasn’t shaken apart in weird ways. He’s led a few! The Unity Squad avoids this fate because Rogue is there to take over when he, uh, turns evil, and she proves to be a better leader than Alex (in Volume 3) to such a wide degree that the previous tenure really stands out as the last gasp of a mediocre reflexive patriarchy. (In more ways than one.) And that’s even adjusting for the fact that she’s also terrible with the media. She’s still not quite as bad at talking to reporters as Alex, and she murders a man on camera during her first press conference.

To wit: there is a notorious sequence near the beginning of the run where Havok addresses the media, during which commences a brief exchange on the subject of prejudice. This climaxes with Alex making a speech where he takes off his mask and appeals to the commonality of human and mutant to lower the temperature in a discussion of grievances. At which point, if you recall correctly, the internet exploded in the general direction of the writer, for reasons which should by now seem very familiar. (This was issue #5 of the first volume, early 2013.) One of the most privileged mutants in Marvel’s stable was trying to steer the conversation away from thorny conflict and towards a peaceful resolution that ended in some kind of agreement on amorphous common principles. Principles which can often seem commendable in a vacuum but which in context become rudimentary and condescending. Refocusing an argument away from specific controversy to general commonality may occasionally defuse tempers in the short term but is much more likely to further entrench misunderstanding, representing enforced amity used as a tool of privilege to muffle dissent. I’m simplifying immensely. What did he actually say?

. . . I see the very word “mutant” as divisive. Old thinking that serves to further separate us from our fellow man. We are all humans. Of one tribe. We are defined by our choices, not the makeup of our genes. So please don’t call us mutants. The “M” word represents everything I hate.

Then a reporter pops up, “Well . . . If you don’t want to called ‘mutant,’ what should we call you?” At which point Alex Summers, handsome blonde All-American Alex drawn with the utmost charm by Olivier Coipel and Mark Morales, cocks his head a little bit and smiles, wryly . . . oh yeah, he’s got this one. Batter up, pitch, swing - “How about Alex?” Home run. It’s Miller time.

The Grim Reaper bursts onto the scene at that point and things get violent. Rogue murders Wonder Man’s brother on live TV but the damage had already been done.

What is interesting in hindsight is the degree to which Alex’s good-hearted but also resolutely clueless inability to engage with any but the most superficial reading of an ideological rift presents a perfect example of this manner of subtle derailment, familiar from a decade of intensifying discourse on these subjects in our own world. The problem in this formulation becomes the conflict that results from the problem and not the problem itself. The only people walking away content from that exchange are people whose goal was not fixing the problem but smoothing the disagreement. Usually just makes things worse.

No one gets the assignment of a huge new launch coming out of one of the company’s biggest-ever crossovers thinking, “oh boy, time to get yelled at by people online!” A common dilemma and a very familiar pattern. The arguments in this comic and around this comic both follow that pattern pretty well. An initial attempt at good faith discourse is marred by pitfalls as the conditionality of that good faith itself is questioned, fairly or no. A defensive crouch sneaks into the discourse partway through the series. Ideological conversations become more deliberate and effortful. There are long passages which read less like real conversations than and more like balanced and researched (if hardly unbiased) polemics. A few issues later (issue #9) a heated conversation between Rogue and Wanda unfolds thusly:

Wanda: No one group owns persecution, Rogue.

Rogue: But telling any group not to be proud of who they are -

Wanda: Alex didn’t tell anyone not to be proud of whom he or she is. Don’t extrapolate your own version, listen and speak to what the man actually said. He was asking people to see the person first . . . and to not judge anyone based on any one trait.

A little later in the same conversation:

Rogue: He’s asking people to forget their history - to assimilate!

Wanda: What history? Assimilate into what?

Rogue: “Normal” human culture.

Wanda: As opposed to what, normal mutant culture?

Yadda yadda yadda, another page later they are still talking and we have clearly entered the “shower conversations with straw men” segment of the program. Rogue ends the conversation yelling,

All I hear is rationalizing from the witch who tried to wipe us out. You ask me, deep down, in the center of your belly, you’re ashamed of what you are - Maybe you do think things a would be better if there were no more mutants?

Points are made? In fairness it probably isn’t to any writer’s strengths to have to deal with massive negative blowback to what was, in the context of the story, a relatively minor thematic sidebar. But therein lies the rub - even if it doesn’t take up much of the story’s running time, a great deal of how people find themselves reflected in these stories depends on just such minor sidebars. People form intense personal connections to different aspects of the core premise of the X-Men, an emotional spectrum that simply doesn’t exist for the Avengers. That’s one reason why those particular arguments rarely produce winners. Rogue doesn’t always come out the best from these arguments and is often portrayed as headstrong (which she certainly is) beyond the point of reason, with vision occluded by trauma and grief. Is she being used as a straw woman to reiterate one side of fraught arguments in just such a way as to allow the writer to explain himself in light of then-recent online discussions? That’s why Campbell’s soup is mmmm-mmmm good.

As I spent a lot of time (probably an otiose amount of time) discussing previously, as awkward as they may be these are still important conversations about the world of the kind that are supposed to take place in X-Men comic books, either explicitly or allegorically. Worth noting again that even Claremont struggled when his series moved past dealing in metaphors and attempted frank discourse on matters of actual social gravity. Everyone remembers Kitty saying the “N”-word, after all, a family favorite from way back. God Loves Man Kills is a bit turgid if we’re being honest with ourselves. The X-Men can be heavy-handed, which is occasionally a drag and sometimes even (as in the examples at hand) tone-deaf and aggravating, but those sensations are themselves part and parcel of the franchise. What I’m saying is, don’t linger too long on these sections and you won’t be disappointed when Uncanny Avengers fails to resolve the racial tensions of a lonely nation. In this respect it’s a representative artifact of the manner in which the national discourse around these thorny topics was beginning to cohere - or, perhaps better to say, failing to cohere - in the early evening of the Age of Obama. The specific individuals chosen to represent those arguments and institutions utterly failed to rise to the gravity of the moment and we still live in the rubble of the consequences.

The book does mount an argument, unwitting or no, as to why these kinds of imbroglio rarely produce satisfying results. In real life terrible arguments stemming from deep divisions don’t also culminate in long adventures where people have to learn to live as a team in order to survive. The Avengers and the X-Men start getting along better because they have to do the work of seeing the world through each other’s eyes and learning to communicate in order to save that world. People in small groups who have to cooperate for immediate survival usually find ways to resolve differences. Absolutely shocking revelation, I am aware. Sadly the solution doesn’t always scale, as recent events in our own world may attest.

Which brings us to the final stretch of the series, after the far more gratifying Apocalypse / Kang thread has wrapped. Yes, I speak of AXIS. Do you remember AXIS? This is what it was all leading towards. And, you know, if we’re being frank, a big reason this series hasn’t lingered in the public consciousness like other runs of comparable quality is that it climaxes in a giant wet fart of a crossover that somehow reads as rushed despite two years’ buildup. The cookie, sometimes that is how she crumbles.

Just what is AXIS , anyway? Why not just ask the me of October 2014, writing for the AV Club?

Whenever the subject comes up, Marvel swears the only reason it does so many crossovers is that people continue to buy them. Check out any of Axel Alonso’s Q&As or Tom Brevoort’s Tumblr, and there are many variations of the same complaint: Too many events! To which Marvel replies: If you don’t buy them, we’ll stop making them. So the phrase “event fatigue” gets thrown around by long-term fans sick of the constant hype machine, but it really doesn’t mean anything, because new events always sell like gangbusters. Someone’s buying them.

Event season is no longer limited to the summer. Event season is now every season. Original Sin preceded Avengers & X-Men: Axis #1-#2 (Marvel), and Axis itself will be supplanted by the conclusion of “Time Runs Out” and a new Secret Wars in the spring. Secret Wars will last the summer, and at some point soon there will surely be an announcement of what the post-Secret Wars fall 2015 crossover will be. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose . . .

Axis at least has the virtue of emerging as the organic conclusion to two years’ worth of ongoing story in one of Marvel’s flagship books, Uncanny Avengers. The events of Axis have been telegraphed since almost the first issue of that series: The Red Skull, having stolen the psychic power from Charles Xavier’s corpse, has somehow managed to transform into a new incarnation of Onslaught, surely everyone’s favorite ’90s event villain.

That this was all Magneto’s fault, and that the birth of Red Onslaught was the direct result of Magneto committing the completely understandable “mistake” of crushing a Nazi to death under a giant rock, is a nice touch. The story tries to throw a bit of shade at Magneto for murdering the Skull in cold blood, but really, implying a Holocaust survivor isn’t justified in killing the Red Skull is an indefensible supposition.

All of the themes writer Rick Remender has woven together over the course of Uncanny’s run are here: humans and mutants cooperating against anti-mutant hysteria, the necessity of forgiveness, and the persistence of memory. The problem is, now that the main event has arrived, the story itself chooses a terrible moment to run out of gas. Would this story have been better if it had been “just” a focused mini-event restricted to the pages of Uncanny Avengers? We will never know.

The “hook” of Axis, above and beyond being the climax to Remender’s run on Uncanny, is that with the heroes out of commission, it falls to the villains to save the day. That’s not a bad hook on which to hang a story, all things considered—and it works here because the Red Skull is one of only a handful of characters Dr. Doom, Loki, Magneto, and even Carnage might put their differences aside to throw down against. If the solicits are to be believed, at some point in the story the world is turned upside down (on its axis, one might say), and the villains really do become heroes. (Rumors seem to indicate Sabretooth will be permanently—or “permanently”—changed enough to join the post-Axis lineup of the Uncanny Avengers.)

That the series is already one-quarter over and we still haven’t gotten to the hook is a problem. So far we’ve seen the Red Onslaught just about murdering the heroes, Magneto gathering a team of the world’s most powerful villains, and not much else. Remender suffers at times for being a deliberate plotter, but the first two issues of Axis read as if Jonathan Hickman took a pass at the scripts to cut down on the amount of interesting events per issue.

It doesn’t help that the Red Onslaught’s great plan amounts to stealing some of Tony Stark’s old blueprints to make adamantium-coated hero-killer Sentinels. (Tony made a lot of really good decisions during the Civil War.) The story reminds us that Tony doesn’t remember writing the plans because his brain got rebooted during “Dark Reign,” which doesn’t do a lot to ameliorate the fact that he should still have known that designing special super-Sentinels has never, ever gone right for anyone in the history of comics. And super-Sentinels remain as interesting an antagonist as they’ve ever been, which is not a lot.

[2021 Tegan: Worth pointing out here that the reason Magneto needs to gather villains in the first place is that, because these Sentinels were designed during the Civil War by Tony Stark, they’re only programmed to fight superheroes. Hence, they are helpless against super-villains. That’s the logic. The Sentinels weren’t programmed to fight villains. That’s the plot. I’m sorry.]

Fans of the original Onslaught saga (God bless them) will find a lot to like here, from the callback to the original story’s use of Sentinels as cannon fodder through to Adam Kubert’s dependable art (he drew the original Onslaught as well). Marvel is getting smart about these events and shipping them in weekly or near-weekly frequency, which is good, because this would be a pretty awful read month-to-month. Retailers will already have ordered the first few issues before they even know if the story is any good, even after having moved the order cut-off date. Good business model.So how will it all end? Hopefully better than Original Sin (which, if we’re keeping track, ended exactly the way everyone knew it would from pretty much the first page). If this writer sounds cynical about the never-ending cavalcade of events, please forgive. A good event showcases a particular kind of widescreen storytelling superhero comics can do that very few other mediums even approach, although Marvel is currently giving it a try themselves in the world of film. Good events are exciting, and even mediocre events can be entertaining. Coming so hot on the heels of Original Sin, however, and with the juggernaut of a new Secret Wars breathing down its neck, Axis needed to be a lot more than this to read as anything more than Marvel hitting their quarterly sales target.

So - yeah. There were two stories in AXIS, neither of them were that strong, and together the whole thing is just kind of a mess. One of them involves the Red Skull becoming Onslaught because apparently it was a bad thing for Magneto to kill him. In 2021 such an assertion is plain silly. In this day and age Captain America himself would probably grab the flamethrower to incinerate the body, because even in the context of the Marvel Universe itself the Red Skull’s ability to come back from literal death is beyond parody. He’s always back. He has a knack for it, even keeps a weird little freak hustling pretty much 24/7 to ensure the process goes as smoothly as possible. (Arnim Zola, if you’re keeping track at home.) Plus, I mean. He builds a concentration camp on the ashes of Genosha. By all means kill the Red Skull. Go crazy, enjoy yourself. Chances are very good you’ll get another opportunity before long.

The two halves of the story seem more ill-fitted in hindsight. Spending so much time on real horrors with close counterparts in our world, a world in which the evils of prejudice and hatred often seems intractable and ineradicable, really sits ill at ease with the idea of good and evil being concrete attributes which can be switched on and off like a light switch by a sorcerer. Which is what happens halfway through Axis. Suddenly the story that was about the Red Onslaught and genocide is about Carnage having a face turn. There’s a high-concept Silver Age feel to that gimmick, and while I’m not saying there’s no place for the occasional high-concept Silver Age gimmick - heaven forfend! - perhaps that place was not the climax to a two year saga of pride, bigotry, and mass murder.

Worth mentioning, before moving on, that Remender’s idea of a heel turn for the X-Men involves the team calling a meeting where they announce they’re all on the same page with Apocalypse and are ready to start playing offense against the human race. Fun sequence, that. Wonder if it ever comes up again.

Anyway. The first volume of Uncanny Avengers was an old-school jam in an era of the new. The second volume is only five issues long and immediately precedes Secret Wars. It’s not a lead-in, its devoted to establishing the Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver’s new origin and it features the High Evolutionary. There’s no acknowledgement of the crossover other than a tiny Secret Wars logo on the very last page to indicate Remender’s time with these characters had come to an end. These comics were always going to be retconned, and perhaps by the time you read this they will have been. It’s not a bad story, in any event, featuring good work from the ever-reliable Acuna and an Avengers team that exists nowhere else, led by Rogue and featuring the Sam Wilson Captain America and the Vision alongside a temporarily good Sabretooth. The team that comes out the other side of Secret Wars bears little resemblance to Remender’s, as we shall see, although Rogue’s and Wanda’s character arcs do stay consistent between multiple volumes, as we shall also see. That’s what we’re here for, after all, and where we can look to wrap it up.

We shall conclude with the observation that Remender holds the distinction of having written the worst line of dialogue ever spoken by Rogue. At the very beginning of the series, issue #2. The occasion for this line was Rogue, held captive by the Red Skull and his cannon fodder mutant animal people S-Men, escaping from her bonds. (The Red Skull’s cannon fodder mutant animal people S-Men are used this one time and never mentioned again, so far as I know), All well and good. The escape was effected by means of a contrivance involving spitting water out of a cup onto a water elemental, a bit of straightjacket dexterity accompanied by the line:

Thank Remy LeBeau and all those kinky bondage drinking games.

Friends, life is suffering. This is known.

This line has haunted me for almost a decade. As the years passed and I forgot much else of this book I still remembered that line, planted like a festering half-popped carbuncle on the ass of my mind. Is that something people would say? Speak those words out loud - does that conglomeration of syllables roll off the tongue or does it trip thuddeningly? Positively Dreiserian in its commitment to describing a hated phenomenon with great precision and a minimum of art. Perhaps people actually do such things, precisely - who knows? It is a large world, filled with depravity. Would anyone ever say that baldly explanatory phrase - “kinky bondage drinking games?” Perhaps this is simply down to the difficulty of conveying the chimera of memory through the meager medium of language. The scene is such that honestly . . . well, I don’t know why drinking from a paper cup without hands is a rare skill, especially as in this instance it involves simply splashing herself with water. Is it? Do you absolutely need to have sex with Gambit to unlearn our parochial flatscan vanilla water drinking habits? Any skill transferred by such means deserves no perpetuation. This place is not a place of honor . . . no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here.

The first volume of Uncanny Avengers was a deeply imperfect book that nevertheless accomplished many important things. In wonkish terms of continuity and lore it may prove more significant yet, given a great deal of road is laid down here that has yet been barely driven. The nature of the book is such that although we speak of it in general terms as being Remender’s story, along with his artists, it’s probable that as much as a little or a lot of the plot and character beats were hashed out in committee. We can’t know, but this was a high profile launch coming out of an enormous crossover. That’s how this world works. I say that neither to castigate nor to exculpate, but to qualify the judgment that this isn’t Remender’s best. Not his worst, either! Thankfully, the wince-inducing crass humor that occasionally mars his work is mostly absent, largely shunted off to a skippable satirical Annual featuring the team crossing swords with Mojo. He’s good at plot-heavy page-turners with strong character beats - as “meat & potatoes” as it gets, for mainstream superhero books. As such this book is best when the pace is fastest and the concept the highest. When it stops to sit around and mull Uncanny Avengers gets lost in its own head. It fails to realize until the end that the real antagonist all along has been Alex Summers’ ascendant mediocrity, and that nothing was ever going to get better without a change of management.

(“Skippable Mojo story” is a redundancy, I know.)

That change of management would soon arrive. After the brief second volume, the third volume of the series that arrives on the heels of the Secret Wars arrives with Rogue firmly at the helm of a new and very different team. The first year of that book coincides precisely with one of the worst years in the company’s history, an annus horribilis that saw Rogue’s unlikely team of Avengers frogmarched through four of the company’s worst-ever crossovers - Inhumans vs X-Men, Standoff!, Civil War II, and, yes, Secret Empire. It is a testament to the strength of the series’ creators, primarily Gerry Duggan, that the book recovers. What could have been a car wreck becomes a trial by fire leading to profound personal triumph for Rogue. What could have easily been a muddled and forgettable interlude instead becomes her finest hour.

________________

Oh, What a Rogue

1. I Got No Clue What They Want to do With You (1995)

2. Hello Again (1990)

3. Make it With the Down Boys

I. Everything is Science Fiction (1963-1983)

4. The Journey Ends

Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV (2012-2018)

& A Few Short Words About Carol Danvers