Oni Love Can Break Your Heart

Queen & Country: DeclassifiedI've a confession to make before beginning this review: there is no genre of fiction as resolutely uninteresting to me as the espionage thriller. I don't even really like James Bond, and even though I realize that the Bond movies are about as far from an accurate representation of the spy world as

Spongebob Squarepants is of invertebrate biology, just the merest whiff of traditional spy genre signifiers is usually enough to make me instantly lose interest.

So I approached

Queen & Country with no small trepidation. For not only was this supposedly a spy book, but from what I had heard this was a

heavy-duty spy book: thick with procedural detail and told with the kind of deadpan naturalism that has over the last fifty years evolved into the default tone for every extant subgenre of thriller. But let it never be said that I am one to shrink from a challenge: despite my ignorance and traditional antipathy for the genre, I was committed to giving one of the most acclaimed genre books of the last few years a fair hearing.

Based on the example of this volume, I will say that Greg Rucka seems to have a natural feel and enthusiasm for the genre. Although I was (and remain, for the most part) ignorant of the specific mythology surrounding

Queen & Country, the narrative is laid out with painstaking and methodical transparency, so that despite my unfamiliarity I knew basically what was going on at every point in the story. This isn't an adventure so much as a procedural, and the permeating sense of creeping moral ambiguity is offset by the absolutely banal nature with which the proceedings are presented. Spying is as much a job here as anything else, and it comes with the same petty politics, backstabbing, and shitty recognition as anything else. So, even though Paul Crocker's job is probably a bit more stressful than yours or mine, it is still recognizably

a job - and this focus on concrete professional details provides effective thematic ballast. Like a particularly well-crafted episode of

Law & Order (not a program I regularly watch but one that I can appreciate), it presents a universe shorn of moral certitude but buffered by the presence of inherently decent and conscientious men.

I have no idea how "realistic" the spy milieu is presented in this book, but the important thing is that it

feels roughly accurate, which is undoubtedly the effect Rucka and Hurrt were aiming at. The mundane, almost aggressively banal presentation of office and field work carries with it a convincing aura of authenticity: there aren't any doomsday devices or fancy gadgets, just men, guns and paperwork. Of course, for all

I know the real spies could very well have fancy gizmos and flying shoes, but again, the visual and thematic milieu of low-tech naturalism is well rendered.

The most enjoyable facet of the book, for me, was the attention paid to historical and architectural detail. If Brian Hurtt's figures sometimes seem rubbery or lacking in dimension, the book excels in the believable representation of physical dimension. The backgrounds are rich with the kind of detail that most artists simply have no interest in rendering: elaborate street scenes, authentic regional architecture and delineated interiors. If I had to guess, I would say that Hurtt had studied architecture at some point in his career, because he seems far more comfortable with the detail-rich world of objects and buildings than with the somewhat less defined world of people. His prowess with the technical pen, as seen on the streets of Prague and the understated interior of the Crocker's residence, is impressive.

Action sequences are often a stumbling block for non-superhero comics: oftentimes, the more realistic the action depicted is, the less convincing it becomes for the reader. Rucka and Hurrt seem to have a good rapport here, because there are some fairly complicated sequences throughout the book that are handled with excellent clarity.

Ironically, the same attributes which make

Queen & Country so blessedly unique in today's market also serve to make it a less than satisfying read for me. As I said, I'm not a spy fan, so while I can definitely appreciate the fact that this is an extremely well-done book, I must also reiterate that it serves a very specific function, which you will either appreciate or not. I have to respect Rucka for producing something that steadfastly resists the industry's seemingly inexorable trend towards hybridization: there are absolutely no concessions made to the authors' purely Platonic ideal of their genre. Considering the fact that the only moderately saleable police procedurals currently being produced in comics all involve spandex, and that the brain trust at Marvel remains convinced that the only conceivable way to produce a romance book is to tie it into Spider-Man continuity, the presence of a doggedly un-fantastic book like

Queen & Country in our domestic comics market is something of a triumph. While the presence of something more in tune with conventional mainstream tastes could conceivably have raised the book's profile, the fact that it remains uncompromised is definitely a point to Rucka's credit.

If the following decades prove fertile ground for the diversification of American comics, then there is no doubt that the spy thriller - after all these years still a staple of mainstream American prose fiction - could very well become one of the medium's most promising and popular genres. If this is the case, then

Queen & Country could stand as the forerunner to a new generation of popular comics, a founding father of the long-foretold "New Mainstream". In a perfect world books like this, with inescapable populist appeal and the kind of engrossing procedural verisimilitude that successfully carries so many popular TV and movie franchises, would sell millions of copies. I guess in the world of comics they have to be content with making their money back from the initial printing.

Solo #3: Paul PopeFor whatever reason, I have never warmed to Paul Pope's work. This has only been exacerbated by the fact that so many of my peers in the comics blogosphere seem to be hopelessly enraptured with him, to the point where a new Pope comic is usually accompanied by all sorts of absolutely specious hyperbole, usually rendered in capital letters and a slightly disparaging air of moral certitude. "Of course, Paul Pope is a genius," they will say, "and as a genius he demands our utmost obeisance!"

Well, perhaps, and perhaps not. He is certainly a capable draftsman, and his compositions are usually interesting, but his faces betray a puckered sameness and his linework is adolescent and overwrought. I wouldn't dream of judging his writing from such an inadequate sample, but there was nothing here to mark him as anything but a journeyman with a flair for understated melodrama. I certainly found nothing to dislike in "The Problem With Knossos" or "On This Corner", but neither were they in any way spectacular examples of their respective genres (mythological pageant and urban slice-of-life).

Of course, it also doesn't help matters that his "tribute" to Jack Kirby, "Are You Ready For The World That's Coming?" is not really a tribute so much as a straight retelling of

Omac #1, right down to the pacing and dialogue. It'd be one thing if it were accurately credited as such, but the credits page clearly states:

"all stories written and illustrated by Paul Pope" - which is a claim that even a cursory examination of the Kirby comic in question will reveal to be bullshit. As much as that grates, you can probably (hopefully?) chalk that one up to missed communication - easy enough, I suppose, to forget a story credit, but if this issue is ever reprinted they need to fix it.

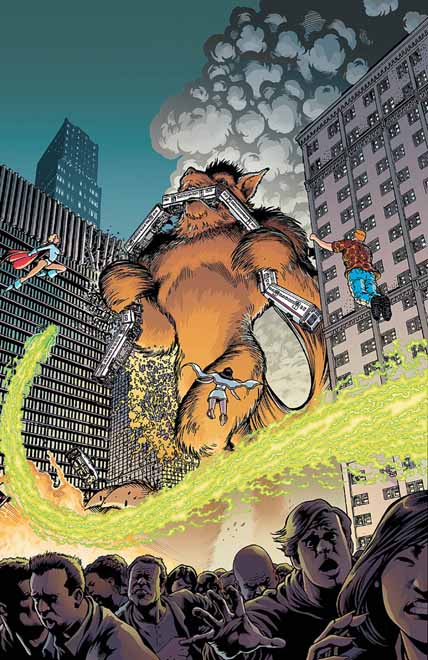

Ironically, the Omac story is the best thing in here, even if a Kirby homage is probably nowhere near the most advantageous light for any young artist to present themselves. It works because Omac was one of Kirby's most deliciously dense and thematically bold creations, a chunk of total sensory overload that puts most of Grant Morrison's attempts to create similarly hyperbolic narratives to shame. Pope's slavish recreation reveals it to be a surprisingly relevant missing link in modern comics history. There's so many ideas being thrown out in every panel, strange concepts and subliminal perceptions, and a not-so-subtle sexual anxiety slathered all over the page in seemingly abstract, barely-representational primal shapes. Of course, Pope falls short of the template, but it is an interesting and fulfilling exercise in that it helps to reveal nuance and power underneath Kirby's own lines. A career composed of this kind of thing would be hopelessly futile, but as an occasional lark this kind of imitation can be instructive and engrossing.

There's a Robin adventure that is notable for the fact this is perhaps the most brutal depiction of Robin being beaten up by thugs I've ever seen. This story also features the coloring of up-and-coming talent James Jean, who produces some remarkably subtle effects with aqueous pastels, very much redolent of Al Columbia's nauseating color work. Definitely appropriate for a story that features a bunch of crooks and a clown-faced psychopath beating up on a fourteen-year-old boy before trying to throw him in an industrial plastic-shredder. Cheery stuff, fun for the whole family.

All things considered, this is an interesting book that still falls noticeably short of the endless hosannas being heaped upon it and its creator. Pope is certainly talented, but his particular appeal continues to elude me. His precociously febrile linework and trout-faced people seem like the hallmarks of an as-yet undeveloped talent with a lot of work yet to go before he outgrows the inordinate stylistic flair with which he has attained his current peak of popularity.