Invasion of the Giraffe WomenBefore we go any further I'd like to draw your attention to an ad I came across recently in

The New Yorker:

This is an ad for some kind of computer thingie from Intel that we'll surely all rush out and not buy tomorrow. I don't spend a lot of time looking at ads (who does?) but I must have spent two or three minutes just staring at this ad. Why?

That woman has a freakishly long neck. I have never seen anyone with a neck that long, save possibly for those African tribespeople who elongate their necks with concentric brass rings you always see in

National Geographic. This is pretty much the definition of a failed ad. Ideally, you would imagine an ad should make a point of drawing your attention to the product in question in a positive manner, creating positive associations or at the very least building product awareness. Now, if I ever stumble across one of these Viiv things, my first thought will automatically be: that is a product for people with freakishly long necks. I like my neck just fine, I think I'd better steer clear. Correlation isn't necessarily causation, but I'm not going to take any chances with the thing that keeps my head from collapsing into my trunk.

I'd like to clarify a couple points I made the other day, in light of some interesting observations Milo made in the comments section.

First, I don't think that there's any overarching chronological plan to Marvel's

Essential line. I do, however, believe that the collected series have followed a more or less chronological order in terms of their releases. The reason for this is simple: the hard core of Marvel's most lucrative properties, with the obvious exception of the Clarement X-Men, hails from the 1960s. When Marvel ran out of Silver Age material to compile -- and I think they've

Essentialized or

Masterworked every Marvel superhero series from the era except for

Sgt. Fury and

Not Brand Ecch -- they moved on to the 70s. Now that they're getting pretty deep into the 70s --

Killraven, for God's sake -- it's only natural they're beginning to utilize more and more 80s material. There's no master design at work other than the fact that Marvel is in the business of making money, and Marvel is obviously going to put their more lucrative properties into print before they move on to undoubtedly less lucrative but still greatly appreciated niche volumes like

Howard the Duck and

Luke Cage. So expect more and more 80s material to show up, as this is an era which has been only lightly exploited in recent years.

(Incidentally, am I the only one who thinks it odd that Marvel has been chronically unable to exploit any of their stable of horror and monster characters these past few years? The success of the

Tomb of Dracula reprints -- and I think it's safe to say they were

very successful, based on the speed with which the entire series, as well as companion volumes for

Werewolf by Night and

Frankenstein's Monster were printed -- shows there's obviously a demand for these characters. Vampires and the like never really go out of style. Plus, the horror genre has had a major renaissance in comics these past few years, becoming probably the most successful non-spandex mainstream genre. And yet, Marvel can't put out a good new horror book to save their lives. It's almost as if they've completely forgotten how to make a genre book that isn't a superhero hybrid -- look at

Sgt. Fury's Howling Commandos [or don't, as it is a horrible, ugly eyesore of a book], look at

Marvel Zombies [which is fun, but not what I'm talking about]. I would be willing to bet -- and I imagine the retailers in the audience will back me up -- that if Marvel put out a good, solid

Dracula book that wasn't a retread of the Wolfman stories and maybe even managed to tie into the real-world popularity of Blade [something else Marvel has been chronically unable to do], it'd fly off the shelves. Hell, Marvel could probably bring back Simon Garth and do decent numbers, considering the current craze for all things shambling and undead . . . assuming, of course, it's not some lame superhero hybrid. [Are there enough Simon Garth stories to make an

Essential? I remember seeing some awesome art from those books, and I don't think they've ever been reprinted before . . .])

Also, it bears repeating for posterity: DC does not have some sort of vendetta against

Sugar & Spike. I merely think the extremely vocal and enthusiastic support the series receive from its many fans is funny. I mean, seriously: DC is in the business of making money. They will not hesitate to reprint something if it will make them money -- but you can forgive me for suspecting that a

Sugar & Spike Archive might not be the biggest money-maker in the company's history. Now, obviously, with the invention of the

Showcase Presents, the possibility of vintage

Sugar & Spike stories returning to print is a lot higher. I still don't know if it'll ever happen... but not out of any hidden agenda on DCs part. It's just not something that I could imagine selling very well outside of a very small and vocal minority who'd probably camp out in front of the shop for it.

But that

might be changing. Dark Horse is bringing a sizeable chunk of

Little Lulu back into print, and Lord knows the

Complete Peanuts is doing well. A market for vintage kids comics apparently exists, even if it requires some prodding. Now,

Sugar & Spike are nowhere near as recognizable as

Little Lulu, let alone

Peanuts, but I can see some overlap.

However, if I may make a suggestion: don't bother publishing a

Showcase Presents Sugar & Spike. Instead, enlarge the art about 150%. Print the books in softcover, about two hundred pages each. Use a comparable paper stock to the

Showcase Presents and print the stories in black & white. But price it at about three dollars and market it as a coloring book.

I'll bet you no one ever went broke publishing coloring books.

A while back ago, if you'll recall, I made a promise to spend some time discussing my favorite Superman stories from the Byrne revamp era. I did not forget this vow, but circumstances intervened. I've spent some time thinking, however, and while I am handicapped some by the fact that 90% of my comics are 3,000 miles away, I have a good enough memory to be able to remember a few key stories.

First, do you own a copy of this comic? Let me suggest that if you care for superheroes at all you need to track down this comic. It's very good, and it's got Eduardo Baretto art, which is very good indeed.

I must admit that, growing up, I thought Lex Luthor was kind of stupid. I mean, sure,

now I get it: Lex Luthor was a badass. He broke out of jail every other week and he didn't even bother changing out of his prison jumpsuit before trying to kick Superman's ass. He had green and purple armor and he flew around the universe trying to fuck shit up. There's something so pure in the concept of a cranky old man who basically wants nothing more out of life than to kill Superman; it's almost Platonic in its purity.

But this is not that Lex Luthor. In fact, this is pretty much the antithesis of that Luthor. This is 80s Luthor at the height of his form, a plutocratic predator who has more in common with a Bret Easton Ellis character than, say, the Toyman or the Trickster. He's a badass, too, but for entirely different reasons than the pre-Crisis Lex.

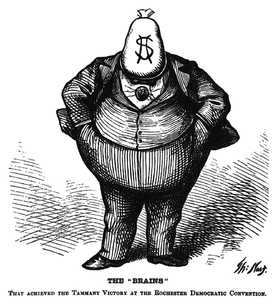

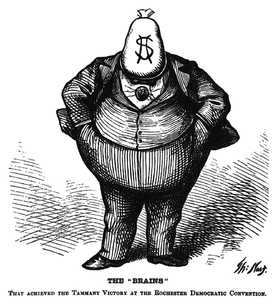

First, the post-Crisis Lex gets a lot of flack for being a Kingpin rip -- which is, I believe, a wholly unfair generalization, considering that

both characters are pretty transparently built off the same visual shorthand cartoonists have been using to characterize immoral, avaracious fat-cats since the days of Thomas Nast. In that respect, I guess you can say that both the Kingpin and the 80s Luthor were rip-offs of the O.G. supervillain, Boss Tweed:

If I had to guess I would say that this book was commissioned as kind-of a companion to

The Killing Joke, in that both books are bookshelf-format spotlights on the company's major villains. This one doesn't get a lot of attention, however, because it doesn't have Alan Moore and it doesn't have the Joker shooting Barbara Gordon. I don't believe there were any major continuity changes or gratuitous violence in this book (although I may have forgotten something): what you have is

merely a good story about how Luthor became a very, very bad man.

Essentially, there are two plots. First, we see Clark Kent being dragged into a police station on suspicion of murder. It's an obvious set-up, a frame, but Kent has no alibi because at the time of the murder he was halfway across the planet saving some brown people or something -- which he can't very well tell the police. Parallel to this, there's also a reporter sneaking through Luthor's back pages, uncovering the brutal truth behind the facade of the "respectable businessman" and pillar of Metropolis' business community. I don't remember exactly how Kent got out of that jam, but I do remember the other reporter comes to no good end (I don't think it's a spoiler to point out that, when messing with Lex Luthor, the odds are high you won't die peacefully of old age.)

Now, the post-Crisis revamp worked so well, in my eye, because it didn't try merely to revamp or redo what had already been done. There was a tacit awknowldgement (or at least, I felt) that changes were being made with a respectful eye to what had worked in the past, and a desire to neither repeat the mistakes that had hurt the character in the first place or to slavishly hew to those aspects of the mythos that

had worked. It was, in every respect, a new beginning, a blank slate with which to try and create a new framework for a character that had grown very, very tired. It's an interesting approach which I think more people who work on these kinds of serialized corporate-generated fictions should keep in mind. It's the same reason I think that, despite it's flaws,

The Ultimates is going to have a fairly long shelf life: it's not necessarily replacing the regular

Avengers, but it is significantly more than just a new coat of paint. It's a wholesale reconceptualization that fulfills both commercial and creative prerogatives. On the one hand, it puts old characters in a new, more contemporary light that enables them to remain at least potentially lucrative, and on the other it gives the people who will make a living writing and drawing the characters' adventures down the road a whole new set of perameters with which to play. The problems occur when, as happened with Superman, the "new" status quo is eventually warped to resemble the old status quo. If you find yourself reintroducing fourty- and fifty-year-old ideas just because you liked them when

you were a kid, maybe it's time to pass the reins to someone younger than you who doesn't have strong personal attachments to every little bit of accrued minutia, and who maybe even has a healthy

disrespect for conventional wisdom...

But in any event, this wasn't your father's Luthor. Whereas old-school Lex was a scientific genius, 80s Lex was smart but not as smart as the people he hired. He didn't get physical. He didn't even have a hoard of kryptonite -- just a small shard, but more than enough. The thing that made post-Crisis Lex such a badass, and which

The Unauthorized Biography illustrates wonderfully, is the fact that he could get away with just about anything. Unlike the Kingpin, whose "humble spice merchant" facade was about as transparent as John Gotti's construction firm, Lex Luthor really

was a respected and beloved community leader. He was also the world's biggest amoral hypocrite. Only a few people, at least on the outset of the Byrne run, saw him as anything other than Metropolis' version of Donald Trump or Steve Jobs. This, combined with his resources, gave him an almost limitless ability to cause mischief, so long as he kept his hands clean.

Which is exactly what he did. This is the man, after all, who got the seed money for his first business by killing his parents for the insurance money. He grew more and more powerful until the moment he first encountered Superman, at which point (the third issue of Byrne's

Man of Steel, I believe), he became obsessed. Not because Superboy burnt off all his hair and caused him to go bald (>snort<), but because Superman had the appearance of being everything Lex was not: incorruptable, honest, and selfless. Luthor knew full well he himself was a hypocrite, that

everyone was a hypocrite, that they all had their price, and that everyone had skeletons in their closet. The fact that Superman was, or appeared to be, not a hypocrite and held no sinister motives, made Luthor seem that much worse in comparison. He was suspicious because (like a true sociopath) he

couldn't understand such transparently benign motivations, and his suspicion made him afraid, and his fear made him deadly.

Luthor was a great villain because he knew exactly how far he could push Superman. He didn't get his hands dirty. No brawling. He

knew that unless he was stupid enough to get caught red handed, Superman was essentially powerless. The most powerful man in the world was bound by a petty morality that Luthor found laughable. Luthor knew that if he had wanted Superman could crush his heart without a second thought, could boil his brain in his skull or just make him vanish off the face of the planet. But he would never do that, and Luthor found this restraint both comical and extremely advantageous.

Of course, this was a delicate status quo that could never last: eventually, they wrote some crappy story or another where Luthor was exposed for his misdeeds. He died and got cloned. He became briefly Australian, had an affair with Supergirl, destroyed Metropolis in a hail of nuclear rain (which is something no one ever seems to mention anymore), got resurrected by a demon (another story which never gets mentioned), somehow managed to regain enough popularity to get elected President, before he became a drug addict and began running around in that silly green and purple suit again. Also, somewhere along the line he (again) became retroactive friends with Clark Kent, and regained a great deal of scientific acumen that, honestly, is just sort of superfluous.

Lex Luthor didn't need to have any sort of personal connection to Superman. He was a great villain in the 80s because he was, essentially, the biggest asshole sociopath on the block. If Superman hadn't come along, he could have just as easily have become fixated on Batman or Green Lantern or the Flash, but as it was he just happened to cross paths with the biggest and bluest boy scout of them all. The big-business corporate milieu might be slightly dated, but there's no doubt that this iteration of the character is a convincing and all-too plausible template: just look at Ken Lay. If Superman gets his main thematic juice from being a representation of everything good and noble about the American dream, why shouldn't his worst villain be a twisted example of that same American dream gone awry, twisted by greed and rapacious capitalism into something wholly evil? There aren't a lot of references these days to Superman's earliest, populist roots -- the guy who threw wife-beaters out of high windows and cracked down on payroll fraud -- and all the sci-fi baggage of the first fifty years served to further distance Superman from the human implications of his adventures. But in the years immediately following the revamp, there were at least some faint signs that Superman had not totally forgotten the lessons of the economic and social tribulations of the 1930s: never trust a rich white guy who presumes to have your best interests at heart.

One last bit of business: a friend is selling a painting on eBay and very graciously asked if I wouldn't mind spotlighting the auction on this blog.

Here you go.