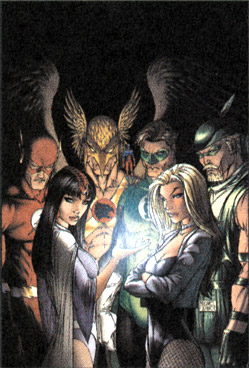

Identity Crisis #2

Whether or not the series is well written is totally beside the point. Whether or not the art is pretty is totally beside the point. Whether or not the characters are in character is totally beside the point.

The fact is, one of the longest running female characters in all of superhero comics was brutally murdered. As if that wasn’t bad enough, she was raped in a flashback in the following issue.

This is a superhero comic, full of brightly clad costumed characters who right for truth and justice. This is the kind of comic book that children would love to read: all the cool characters from all of DC’s coolest books, together in one place and kicking ass. And yet, somehow they have taken the unmistakably wrong step of taking their superhero universe forever out of the province of children’s entertainment and into the realm of brutal, misogynistic snuff books.

It would be one thing if this were a Vertigo book. It would be one thing if this were labeled a Mature Readers book. But it’s not. This is a general audiences book. Did anyone notice the fact that Identity Crisis hasn’t carried the Comics’ Code Seal of Approval? The Seal never really meant much, but DC made such a big deal out of keeping it after Marvel dropped it. Most DC books still carry the Seal, but not Identity Crisis. Isn’t it a bit odd that the biggest thing to happen to their Superhero Universe since . . . well, probably Zero Hour . . . shouldn’t be read by the target audience for most of their superhero comics in the first place?

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not going to tell you that you can’t tell superhero stories that deal with mature themes. But I don’t think it’s really appropriate to have the Flash and Green Lantern and Hawkman mulling over the morality of lobotomizing rapists. I don’t think its appropriate to have a big bright superhero story where a prominent female character is brutally raped on-panel.

Do you want to explain to your child what is happening in these panels? Do you think it’s appropriate for DC to abdicate their responsibilities in making children’s comic books actually child-friendly just because kids don’t buy the books anymore? Well, its obvious from this that they don’t want kids buying the books, because there is no way any responsible parent is going to let a young child read this comic.

Comic book villains have grown coarser and harsher since the 80’s. The stakes have been raised. There is no better way to get to a hero – at least for a few issues, until the death is conveniently forgotten - than the death or dismemberment of a loved one.

Of course, Gwen Stacy died first. But somehow, as bad as that was, it was acceptable in the context of the story because it was obvious that it was an unbelievably Bad Thing. Furthermore, Norman Osborn paid the ultimate price for his crime one issue later. But things went downhill from there.

Barbara Gordon was shot and crippled by the Joker.

Alexandra DeWitt, Kyle Raynor’s girlfriend, was murdered and stuffed in a refrigerator by Major Force.

Vesper Fairchild. Sarah Essen. Joanna Pierce. Donna Troy. Jean DeWolff. Queen Hypollita. Betty Banner. Karen Page. Mockingbird. Hell, even Ultimate Gwen Stacy.

Do I have to go on?

I’m not the first person to mention this. I’m not even probably the one-hundredth. But there’s something wrong here, something very, very wrong.

What is wrong with this industry? Why is it considered OK to kill, maim and rape females by the boatload, when most male supporting characters breeze on by?

But most importantly, why is it OK to have a graphic rape scene be the centerpiece of your massive intracompany crossover event?

It’s not. Period.

(Of course, if you want the whole depressing litany, check this out.)

(And seriously folks, what is the big frikkin’ mystery here? Does no one remember the last Big DC Event, Batman & Superman #1-6? Here’s a hint:

It was L*X L*TH*R!!! People, it's not that hard!

Oh no, I just gave away the mystery! I hope in doing so that I saved you some hard-earned money. And no, I didn’t actually pay for these books myself either. Neither should you, they’re exploitive crap.)

Travels With Larry Part XVI

Ursula

I am torn by this book.

On the one hand, Fabio Moon and Gabriel Ba are obviously very talented. I don’t know how they manage their division of labor, but the end result is a very smooth and likeable product. Occasionally, they get a bit ambitious with angles and POVs, but such stylistic missteps are hardly hanging offences.

On the other . . . I think their story is callow and unconvincing. If I didn’t know, I would have guessed that Moon and Ba are young. Sure enough, they’re just twenty-eight. They seem to have a clear understanding of the kind of stories they want to tell, but a faltering instinct as to how to actually go about telling these stories.

Ursula is the story of Ursula and Miro, two children growing up in a magical kingdom. From an early age they are affectionately in love with one another. Then, Ursula is forced to leave Miro, and return to her kingdom. Miro grows up as the prince of his father’s realm, and when the time comes for him to choose a suitable bride he leaves in search of Ursula, who we have just learned is actually a fairy.

I can see what they’re trying to do. They’re trying to craft a fable, a modern-day fairy tale on the nature of true love. They want the reader to walk away in a romantic swoon, swept away by the passion on display.

I can see the bare bones of this, but they just don’t have the chops necessary to pull it off properly.

In a story, everything has a reason for happening. It may seem unfashionable to talk about narrative in terms of nuts and bolts, but I’m not giving away any magic tricks here. One thing happens because of another thing. Cause creates effect.

There are no real obstacles keeping the lovers in Ursula apart. They separate when they are young, but they come together again at the end. They have a couple problems, but really, nothing worth mentioning. They are absolutely convinced at every step of the power and purity of their bond, and this has the unfortunate effect of rendering everything that passes from about page 10 to about page 70 moot.

One of the great existential problems in art – all art, not just comics – is the question of how to communicate momentary, transformative epiphany. We’ve all seen movies about artist where a painter is struggling in his studio, grappling with some intense creative dilemma. They have a furrowed brow, they steam and fuss and act generally upset . . . and then, blammo, there’s a lightbulb over their head and they somehow, in an instant, get it.

The problem is not that the world doesn’t work this way. It does. The problem is that that showing why and how someone changes their mind, or has a creative epiphany, or falls in love, is almost impossible. This is why Crime and Punishment is still such an important work in the history of literature, all these years on. But it’s also slightly depressing. Character is, and remains, absolutely indefinable.

So, most stories wisely don’t deal with the intangibles of character. Most authors – even brilliant authors – avoid the subject altogether (to say nothing of the postmodern insistence that all art be funneled through the restrictive prisms of mimesis and semiotics). Fairy tales and fables, because they mostly hail from a time before naturalistic character examination became fashionable or even conceivable, tackle character on faith: that is, there is faith on the part of the author and the reader that character is a tangible and unchanging attribute. Characters in fairy tales act on their motivations as a matter of autonomic reflex. There is no hesitation. There is no waiting fifteen years and saying "Oh yeah, I loved that little girl that I haven’t bothered having any contact with whatsoever since she left". Even Romeo and Juliet knew how to write letters.

Which brings me to the problem at the heart of Ursula. The book doesn’t play fair with readers because, ultimately, things happen for no reason and the characters ring false. If Miro loves Ursula, why did he wait until they were both grown - from the looks of things in their mid-20s – to track her down? She’s obviously not in school anymore. She’s working in a bar by herself. If his love for her was as solid and unyielding as we are supposed to believe, why didn’t he do anything until his father told him it was time to find a mate?

All these questions point to instability at the very center of Moon and Ba’s conception of romantic love. We just aren’t given any reason to believe that these two people want to be together, other than the fact that they say they do. How do you communicate such an indefinable feeling, such an intangible and incommunicable character trait? Through action.

Lets look at Snow White. There’s not a lot of deep character examination here, but the characters are perfectly believable at every step of the line. Snow White is awakened from a death-like sleep by Prince Charming, because she has been waiting all her life to be delivered by a handsome prince, in one way or another. She was singing about it at the beginning of the movie. It makes perfect sense in the context of Snow White that a magic kiss would restore the sleeping maiden to life and that they would instantly fall in love and live happily ever after. She wanted to fall in love because every thing that happened to her in the course of the story illustrated the fact that she needed someone to love her, to save her from situations both demeaning and perilous.

But Ursula puts the falling in love at the very beginning of the story. This isn’t a very effective plot mechanic because, ultimately, if we are supposed to believe that they are in love, then nothing else should matter. And yet many, many years pass before they are reunited.

When he finds Ursula, we learn that the reason for her absence all these years is that when fairies fall in love they explode. Um, OK. She explodes, and yet no one is hurt. There are at least three people and one bird caught at ground zero of a two-page explosion, and yet none of them, even the girl who exploded, are harmed. In fact, it isn’t even mentioned that she appears to have destroyed an entire city block.

And instead of answering for his absence by performing a great deed, he basically hops aboard a helicopter and goes straight to her. Sure, he’s caught in an explosion, but that’s hardly a massive feat like slaying a dragon or something – he is caught unawares and, anyway, no one is hurt in the conflagration to begin with. Anyone can get caught in an explosion, especially if they’re magic explosions that don’t hurt people. And if they don’t hurt people, um, what’s the big deal?

Couldn’t this have been covered in a letter? They’ve given the story an indefinable time period, with high technology and modern fashion commingling with mythical elements such as fairies and talking birds. Don’t they have a post office or telephones or even fax machines? Why was someone who was considered fine enough stock to be a childhood companion to a royal prince stuck tending bar in a small diner?

All of these little problems add up to a very big problem, and that is the fact that this story just doesn’t hold together. All the pretty pictures in the world don’t mean anything if you have based your story on a faulty premise.

No comments:

Post a Comment